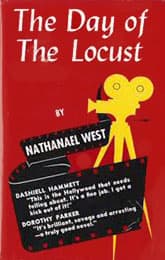

The Day of the Locust

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionThe Day of the Locust

First publication

1939

Literary form

Novel

Genres

Literary, satire

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 52,500 words

Faye Greener (Karen Black) outside a Hollywood star's home in 1975'sThe Day of the Locust.

Too dark for the screen?

The Day of the Locust (1975): Film, 144 minutes; director John Schlesinger; writer Waldo Salt; featuring William Atherton, Karen Black, Donald Sutherland, Burgess Meredith, Richard Dysart

The film of The Day of the Locust had better timing than the 1939 book it was based on when its dark vision was first presented to the public. By 1975 the so-called new Hollywood, with its grittier depictions of modern life, was peaking. The cultural shifts that had occurred since the 1960s would seem to leave audiences receptive to a story that demythologized one of our most glamorous institutions and exposed the veins of violence running beneath the surface of the American Dream.

You'd think so. But The Day of the Locust met with mixed reviews and meagre audiences.

Part of the problem may have been that none of the characters are likable. There's nobody a viewer can root for—a bigger problem for a mass market movie than for a novel.

At first one can identify with Tod Hackett, played by William Atherton as our bland guide to all the degeneracy and falsity around him in old Hollywood. But the first third of the screenplay stretches out his lustful pursuit of the self-centred Faye Greener, alongside other losers she keeps hanging on, until we tire of it.

Not that we tire of her so quickly. Karen Black lights up the screen in a way her wannabe actress character is unable to. Her off-kilter charisma and slightly cross-eyed look add dimensions to what could be just a bubble-headed floozy. But Faye's superficial charms too begin to pale as she continues to use everyone around her without coming any closer to achieving her Hollywood dreams. In fact she seems to fall further off the path she has set for herself, resorting to prostitution at one point.

Much has been made of Donald Sutherland in the role of the shy and moderately wealthy Homer Simpson, who takes in Faye in a "business arrangement", though it's hard to see what he gets out of it. Like others, Homer's a sympathetic character at first, bamboozled and persecuted as he is by assorted entertainment lowlifes. But he's too nervous and repressed to be an anti-hero we can cheer for and he's eventually revealed to harbour a vicious rage.

Trailer for the film of The Day of the Locust, which pretty well tells the whole story.

Then there's Faye's father (Burgess Meredith), a deluded former vaudevillian reduced to hawking bogus furniture polish door to door. And movie art director Claude Estee (Richard Dysart), Tod's mentor, who also indulges in unsavory activities.

Others take us to cockfights, pornographic film parties, a brothel featuring failed actresses, and attempted rape in the hills of Hollywood.

Somehow all this ugliness is easier to appreciate in a book. When we're reading, it doesn't make us wince or cringe as we do when it's thrust upon us visually and abruptly.

It's also hard to accept the story as evolving on screen. Characters in the film seem to be going through their paces as outlined for them. They have their happy moments, their outbursts and their meltdowns when it's time for them to do so. Perhaps the script should have concentrated on fewer characters, fewer incidents, and worked on developing some depth, so we would more naturally accept the motivations for their actions.

Old-style fakery

Then there's the climactic riot. As viewed through Tod's eyes in the novel, mixed with his artistic vision of the burning of Los Angeles, the scenes are apocalyptic. Somehow in the movie they're kind of corny.

Corny for a 1975 production. For a 1940s audience, such scenes as they are filmed here would be horrifying. But we've seen real riots since then and this does not look like any of them. Amid the rampaging mob, the insertion of drawn people from Tod's artwork is also pretentious. This all looks like an old Hollywood kind of fakery, just what The Day of the Locust is supposed to be exposing. (Wait a second, could it be that director John Schlesinger is purposely presenting an implausible finale to the movie to underline the novel's critique of Hollywood unreality? Naaah.)

This is one of the parts of the novel translated almost literally into cinema. The rest of the film is about fifty-fifty—about half following Nathanael West's novel closely, and about half modifying scenes drastically or creating entirely new scenes. And there's no rule for which approach works best. Some of the faithful scenes work brilliantly and some don't. Same with the more original segments.

The writer and director are to be commended for this attempt to adapt this one-of-a-kind novel. Whether following the book's text closely or wildly innovating, they seem to have been focused on getting across the spirit and the significance of West's written work in the film medium. For the most part successfully.

But at nearly two and a half hours though, The Day of the Locust could afford to drop some of the parts that drag, that don't contribute to the story, or that don't translate West's vision into cinematic terms.

— Eric