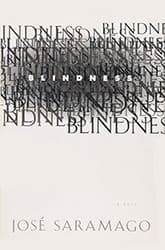

Blindness

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First U.S. edition

First U.S. editionOriginal title

Ensaio sobre a cegueira

First publication

1997

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary, post-apocalyptic

Writing language

Portuguese

Author's country

Portugal

Length

Approx. 134,500 words

What we see in the light

Blindness may be the most popular of José Saramago's novels, possibly because it is one of his easiest to get into. From the beginning the plot reads like a science fiction story—one of those tales in which a virus or unseen enemy gradually takes over humankind.

But rather than focus on humanity's resistance to this mysterious phenomenon and scientific attempts to overcome it, the narrative follows a small number of victims who band together to survive the developing apocalypse. As in an early J.G. Ballard novel, like The Crystal World, the cause of the disaster and its solution are irrelevant to the psychological story of the people in the grip of the disaster. The disaster itself becomes almost of symbolic value.

The disaster in this novel, of course, is that blindness spreads among the inhabitants of an anonymous city (and presumably in the rest of the unnamed country and beyond, though this is never stated). Strangely, they are not enveloped in darkness but rather in light, visualizing only a creamy whiteness.

Only one person in the novel follows keeps her eyesight. However, the person identified only as "the doctor's wife" tries to keep this secret while she is interned in an asylum with her blinded husband. She ends up leading him and a diverse band of unseeing inmates in trying to keep themselves alive and seeking their freedom.

If Blindness starts out as an enticing page turner—a bit of speculative fiction, a bit of mystery, a bit of a survival story—it soon turns into something darker. The so-called asylum becomes a hellhole of human filth, starvation, rapacious attacks and murder. Life becomes equally precarious outside as society crumbles into chaos.

But it's not all Lord of the Flies. The novel develops the sometimes hostile but sometimes warm relationships of the members of the band it follows, without ever naming them (except as "the doctor", "the first blind man", "the car thief", "the girl with the dark glasses", and so on). Within and without the group, characters are occasionally capable of acting with humanity.

What to make of it

The elephant in the room with any discussion of Saramago's work is his style—with long run-on sentences, unconventional punctuation, missing quotation marks and sudden changes of perspective. But the writing is colloquial and the power of the story is enough to soon overcome any initial reluctance to read through the dense pages.

In fact, both the obscuring style and the lack of names or specific locales tend to make the story more intriguing and make any details we are given take on a nearly mythic quality.

How the story ends—not in the way you likely expect—is almost as perplexing as the beginning. Though somehow satisfying. (And, by the way, the 2004 sequel, Seeing, doesn't help much either as it goes off in different directions.)

And what are we left with? It seems too easy to say the entire novel is an allegory, some pseudo-profound parable about our blindness to reality in society. We have sight but we don't see, we see but we don't observe, et cetera. Yet, there's support for this in the book's epigraph and in other quotes from the novel.

Or, to take the science fiction or fantasy approach, is this just a what-if, to examine how we would respond to the loss of an ability we take for granted? An experiment to illustrate the fragility of our social structures?

Or is it, like other stories you can probably think of, about stripping away something that helps make us human in order to see (so to speak) what's left beneath, what deeper features make us humans together?

Speaking of many things

In his Nobel Prize lecture, Saramago said he "wrote Blindness to remind those who might read it that we pervert reason when we humiliate life, that human dignity is insulted every day by the powerful of our world, that the universal lie has replaced the plural truths, that man stopped respecting himself when he lost the respect due to his fellow-creatures."

I'm not sure that really shines much light on what Blindness accomplishes for most readers, though it may indicate the vaguely political hopes the author had for it.

I'm not one to go along with the uncritical shibboleth that a piece of art is whatever you make of it. Some interpretations are not viable. If you think Blindness is a history of a viral epidemic, or a warning about the need to protect citizens' eyesight, or an elaboration of the maxim "in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king"—well, you're obviously wrong.

But I do think a work of art, especially a great book, can be about many things, some of which are more apparent to different people in different times and places. A question may arise that, sure, it's about a lot of things but what is it mainly about? But even if there is a main thing it's about, what are the chances that you—with your singular perspective in your singular time and place—will necessarily get that from your first impression? You need to start with a cloud of insights.

Which is why you should read and listen to what others have to say about a book like Blindness, and most importantly, if you think it really is a great novel, read it again over the years.

That's what I'm going to do before I pontificate any further on this novel of enduring mystery.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies