Gaudy Night

Critique • Quotes

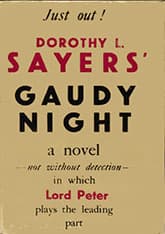

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1935

Literary form

Novel

Genre

Mystery, crime

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 136,000 words

The mystery is how it works so well

British mystery authors like to place their imagined crimes in the hallowed halls of distinguished universities. Maybe they hope uncovering wickedness in the English and classics departments distinguishes their work as literature with literary values and gives their detectives—and, by extension, themselves—opportunities to display their learning.

But when you start one of these academia-centered mysteries you have to dread the coming pages of implausible crime among the intelligentsia, details of dry research by the suspects, the bandying about of quotations from dead poets, reminiscences of past glories from when the lead character was a student, regrets for how the scholarly life has changed, and ultimately a far-fetched solution to the implausible crime.

Dorothy L. Sayers presents all these sorry elements in Gaudy Night, set in a fictional women's college at Oxford University.

But somehow it works.

Of course Sayers is acclaimed for having in novels like this moved the mystery genre into the literary mainstream, while other critics have justly attacked the writing for being too self-consciously literary. The sometimes convoluted stylistic flourishes can be annoying, along with the classical references and passages of poetry. Gaudy Night is sprinkled with untranslated phrases in the original ancient languages, as well as obscure terms only old university habitués would be familiar with. I couldn't understand a climactic marriage proposal and reply until I looked up the Latin they were expressed in and found the exchange was one used in institutional governing bodies to seek and give assent to propositions.

The novel's title, by the way, is a now obsolete name for a college event, something like a homecoming. Harriet Vane, who in previous novels has been the love interest for Sayers's amateur sleuth, Lord Peter Wimsey, returns to Shrewsbury College at Oxford to attend the event and incidentally witness the strange goings on at the institution.

That first-edition cover that advertises "Lord Peter plays the leading part" misleads. The aristocratic detective is not even in most of Gaudy Night, as he is supposed to be involved in some European intrigue.

For more than half the novel, Vane investigates on her own, giving the mystery time to deepen and the suspense time to build. This writer's ploy is similar to that in The Hound of the Baskervilles when Arthur Conan Doyle leaves Dr. Watson floundering on his own for most of the narrative until Holmes swoops in to clear up matters. Frankly, it is a relief to be free of the insufferably jolly and too-perfectly capable Lord Wimsey and to muck about in the mind of a lesser being for a while.

Forget the mystery

Vane, purportedly a well-known mystery writer, is obviously a stand-in for Sayers. Vane is struggling to make her writing more psychological, more realistic, somewhat as Sayers seems to be doing. Much of the novel is Vane giving vent—at least in her unvoiced thoughts—to her mildly conservative views on religion, literature and education and her mildly progressive views on class and relations between the sexes. Sayers has been hailed as a feminist for her character's insistence on women standing on their own feet and her resistance to being seen as obligated to Wimsey. (Although this may be undercut somewhat by the lord solving the case she can't.)

The mystery itself is forgettable. No murders take place, only a series of destructive pranks and poison pen letters that nonetheless drive the dean, dons and residents of Shrewsbury College to distraction (and one student to near-suicide). The misdemeanors are all carried out—incredibly—without any witnesses and with seemingly magical powers of physicality.

The logic of the case's solution is, as usual, somewhat stretched, but by then few readers will care. Vane's inner struggles, her ambivalence about scholarly pursuits, and—especially—her evolving feelings about Wimsey are more interesting.

If this makes Gaudy Night more literary mainstream than Sayers's previous works, then so be it. It's still not one of the great pieces of literature in the twentieth century. And for crime buffs it's a bit of a bust.

I'm still not sure how Sayers pulls it off, given the evidence of so many elements that should count against it, but for open-minded readers Gaudy Night proves an engrossing novel.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes