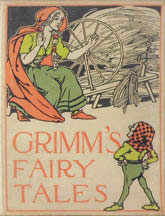

Grimm's Fairy Tales

American edition, 1898

American edition, 1898Original title

Kinder- und Hausmärchen

Also known as

Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales; Children's and Household Tales

Publication history

First edition, two volumes, 86 and 70 stories, 1812 and 1815;

second edition, three volumes, 170 stories, 1819 and 1822;

third edition, 1837;

fourth edition, 1840;

fifth edition, 1843;

sixth edition, 1850;

seventh edition, 210 stories, 1857

Literary form

Story collection

Genres

Folk tales, fairy tales, fantasy

Writing language

German

Authors' country

Germany

Length

Seventh edition approx. 325,000 words

So you think you know these stories?

Take "The Frog Prince". It's about a beautiful princess who kisses a frog to turn it into a handsome prince, right?

Wrong. The princess is a petulant, promise-breaking brat who tries to get rid of the frog by smashing it against a wall. Only then does it transform into the prince and—unaccountably—fall in love with her. At least according to the Brothers Grimm. And then there's a subplot tacked onto the end of the story about the prince's faithful servant who had metal bands placed around his heart to keep it from bursting, which you may not remember reading in childhood.

As you go through the tales collected by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, you'll rediscover many "fairy tales" you thought were familiar from bedtime stories, picture books and cartoons. "Cinderella". "Little Red Cap" (better known today as "Little Red Riding Hood"). "Hansel and Gretel". "Rapunzel". "Little Snow-White". "Rumpelstiltskin". Plus a bunch of tales you probably know collectively as "Tom Thumb".

In many cases you'll be shocked at how different the original German folktales are. The versions you know may have been based on these translations from the Grimm collections but have been bowdlerized, cleaned up, smoothed out and generally Disneyfied. Some of these stories are quite a bit rougher, even crueler, than you thought. The sudden, casual brutality can catch a modern reader unawares.

Then there are the grisly stories you may not know, like the much admired (I'm told) story "The Juniper Tree" in which a stepmother decapitates a boy and makes him into a stew that is served to his father. Or "The Girl Without Hands" whose appendages are chopped off by her father to keep her from evil.

Or others that haven't been repeated as nursery tales because they were too violent or because they rewarded cunning and greed, rather than virtue and modesty.

Or some that have been neglected because, although they once struck chords with superstitious medieval folks seeking escape from their lives of misery, they're just too weird for us today.

Against the one per cent

But they're still great fun to read. Partly to see how we've changed from the people several centuries ago who first enjoyed these fanciful stories. And partly to see how we are the same. A great many of the stories, for example, take for granted that pretty people are good and ugly ones are bad. How much have we thrown aside such judging by appearances?

There is also a love-hate relationship with the elite of society, which makes sense when you consider the downtrodden peasants who originated these tales. They take great delight in having commoners, such as The Brave Little Tailor, outwit their social betters, tricking kings into giving them princesses in marriage, and so on. (There sure were a lot of kings in those days willing to give away their daughters for any jacks who could carry out ridiculous tasks, like killing a dragon, eating a mountain of food, or telling a good joke.)

At the same time, many other stories present royalty, usually in the person of the fabled prince charming, as rescuers, raising the lowly to high position as reward for long, virtuous suffering. Sounds corny and contradictory, but is it any different today? Our culture revels in the escapades of the common man who snubs authority, while it simultaneously adulates our own elite.

It's also interesting to note that most of the evil women in the stories are stepmothers. Apparently these stories originally featured evil mothers, but the Grimms—especially Wilhelm who did most of the rewriting—thought this brought the Christian institution of marriage into disrepute and they changed the evildoers into familial interlopers. The brothers are also said to have tried, after their 1822 edition, to make the stories more suitable for young children in subsequent editions. It seems that even in the 1800s these stories were being recast to suit the current morality.

Other misconceptions about "fairy tales" are also demolished by reading these tales as collected by the Grimm brothers. Few of the stories, for example, involve fairies. The good magical figures tend to be fish, birds, other animals or odd men of the forest. Mundane objects, like buttons and knapsacks, are infused with magical powers. Or sometimes magical spells are brought about without agency—someone just wishes for something and it happens.

Even the story that you might think the ultimate fairy-godmother tale, namely "Cinderella" (called by Kurt Vonnegut the most popular story ever told), does not actually have a fairy-godmother in the original folktale. (No carriage turning into a pumpkin at midnight either!)

Many more tales centre on witches, wolves and an awful lot of plucky lads named Hans.

Also a large number of stories begin with a soldier being decommissioned after a war on behalf of some lord and seeking his fortune as a civilian. It must have been a common problem in the Middle Ages, ex-soldiers roaming the land after the various feudal battles.

The fairy tale formula

You'll notice many other repeated plot elements as well. The three impossible tasks that must be completed to win a reward. The king who promises his youngest daughter to whoever saves the kingdom. In fact, several schemes have been devised to categorize all folktales, such as these, by their narrative elements. Some of these schemes have hundreds of categories and give the idea that all such tales are constructed by merely putting together, say, items #34, #49b and #265i and, voilà, you've got a new folk tale. Of course, this does not account for why some stories get stuck in our minds and end up lasting for generations, while others are quickly forgotten.

Not all the Grimm tales are memorable. Especially near the end of the collection, many of the very short stories appear fragmentary and uninteresting, hardly worth recording. There are many more gems however throughout the collection—both famous and lesser-known tales.

None of the stories actually begin "Once upon a time", unless a translator decides to use that supposedly traditional expression opening instead of just "once", or "in olden days", or "many years ago".

Living happily ever after, though, is definitely the preferred ending. So is the punishment of the villain, often a shrewish woman or witch whose eyes are pecked out by birds or her body pickled alive. (Oddly, however, the wicked occasionally win out in the end. Far from having "fairy tale" endings, some of these stories are quite cynical.)

There are many, many different translations of these stories, based on the various editions rewritten and expanded by the Grimms throughout their lifetimes, or based on later versions by other editors. Books of Grimm's tales on the market today often don't tell you who the translator was, when the translation was done or what German edition was being translated. They are all valid in their own contexts however, and you might enjoy comparing different versions of the same tales, but the volume considered most definitive is the seventh and most complete edition published by Jacob and Wilhelm in 1857.

This seventh edition includes two hundred folktales, plus ten "children's legends" that tend to be more explicitly religious. The stories are numbered from 1 to 210, although some translations do not include the numbering and may change the order.

There also exist some modern volumes that add stories found by the Grimms but not included in the editions put out in their lifetimes. As many as two hundred and fifty stories exist—although the added tales tend to be slender items or variants on stories already found among the two hundred and ten.

Unreal expectations

Tips for appreciating these tales:

Put aside your realistic expectations of literature. In modern fantastical works the magical elements may be explained—introduced in a way that helps us accept them in the universe of the story we're reading, but in these fairy tales they're just given: "A little bird heard her crying and gave her three wishes...." They don't make sense in a larger scheme: why would Tom Thumb get a job to make money when he's not even big enough to carry a coin? But for once don't think about it critically this way. When someone starts telling you a joke with "A dog walks into a bar and says—," you don't protest, "Wait a minute, dogs can't talk"; you just go with it, accepting the silly premises for the sake of the pay-off, the eventual punch line. Approach these stories the same way. The magical elements are not the points of the stories. They're just there as devices to get to the real points: nastiness punished, pretensions crushed, the fun a rascal can have, the mighty brought low, wits triumphing over wealth, and other lessons learned.

Don't read them all at once. They'll tend to blend together, their impact will dissipate and you'll soon forget most of them. Better to read one or two—they're mostly very short—and then put the book aside till next time. Imagine being told the stories a few every night around a hearth or bed a few centuries ago. Keep dipping into them throughout your life. Many of the tales you won't get right away. Some seem too silly or too remote from your modern experience. But give these old stories time to resonate.

And be nice to your mother-in-law.

— Eric