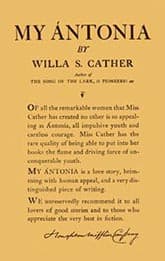

My Ántonia

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1918

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 90,000 words

The gentle letdown

It doesn't sound promising. Like one of those dreary, early Canadian novels some of us had to read in school about settlers in rural North America. Immigrants set up house and farm in the new land, discover the country is harsh, the weather unforgiving. Some overcome hardship, others don't.

But forget all that. My Ántonia is a delight.

The title character is Ántonia (stress on the first syllable as in Antony) Shimerda and, while all that pioneering stuff does happen to her mid-European family in rural Nebraska, she and her friends are interesting enough to keep you turning the pages as you laugh and weep your way through their growth from children to adulthood.

The story is narrated by an American-born male friend who gains success in New York but reminisces about the unsophisticated girl he has been in love with since childhood.

If the writing reminds me of any other writer, it's Maxim Gorky in My Childhood, his memoir of growing up in a Russian village. This may seem a stretch—early twentieth-century American and communist writers are seldom compared—but there are definite parallels in the hard-scrabble experiences of their subjects. Both these writers knew the harshness and cruelty of plain folks, as well as the heart-filling kindnesses of the same. And both these writers could evoke people and places so well that they become your own friends and your own homes. Their ordinary stories become tremendously moving.

Also, like Gorky's memoir, Cather's work here is episodic. The novel, if that's what it is, consists of five sections stitched together from shorter stories. But the character of Antonia, seen from the perspective of Jim Burden the narrator, holds them together—even through the third section from which Ántonia is largely absent.

Ántonia is the third of a trilogy of novels by Cather about strong women who settle the American prairies—after O Pioneers! and The Song of the Lark—all of which seem to end on bittersweet notes. All are acclaimed, though Ántonia is often considered her greatest novel.

However, much as I appreciate Cather's writing here and elsewhere, I find the closing chapters of My Ántonia somewhat pat and sentimental. Far from the social (and even further from socialist) realism that may be expected in such a clear-eyed account of a rural working woman's life.

However, Cather is too realistic to provide the happy ending that one might secretly yearn for. She does let the reader down very gently indeed.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes