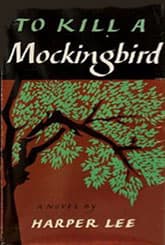

To Kill a Mockingbird

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1960

Literary form

Novel

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 104,000 words

Of time, place and race

Anyone reading Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird for the first time may be surprised to find it is not entirely about racism. The trial of a black man, Tom Robinson, on a spurious charge of rape, for which the novel is famous, does not become a focus of the plot until about midway. In fact, blacks as a whole are invisible for most of the first half of To Kill a Mockingbird.

In the early going, you could question whether the novel is about racism to any great extent at all.

The fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama, in which the case unfolds is drawn so well—so lovingly, despite the unsparing revelation of its hideous racial sentiments—that when you get to the parts touching on race they can come across as being specifically about racism in the American south at that time. We can tear up over the great injustice being done to those poor black people down there by those ignorant white folks back then.

Meanwhile, life in the white part of town goes on languorously in much of the novel as experienced by six-to-nine-year-old tomboy Scout, whose father Atticus Finch is, incidentally, appointed defence lawyer in the rape case. At times it seems this story of the town could stand on its own as a Southern Gothic-lite tale seen through the eyes of a precocious child. The eccentric local characters, their benevolent alliances and their petty rivalries.... the feel-good themes of neighbourliness, of not judging by appearances, of sticking with family.... with the main plot focusing on the evolution of the children's relationship with the mysterious recluse Boo Radley. It wouldn't be nearly as impactful, but it could be an interesting enough, slightly spooky, read.

Generous and nasty people

This conjecture may seem to imply a criticism of To Kill a Mockingbird, a complaint that Lee is distracting us from the very important theme of racial injustice in the United States, engaging us in a sort of Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town in the Deep South.

Far from it. This is actually pointing out Lee's genius in To Kill a Mockingbird. There are both generous and nasty people in every community, regardless of heavy social issues. There are open-minded and close-minded people. There are empathetic and self-centered people. And there are folks—probably a majority—who have both sides warring within them. Moreover, we continue to have the rites of growing up and the struggle to fit into functional and dysfunctional families. Lee's brilliance in this novel is to show all this with the scourge of racism rampant in the same society, an unspoken part and parcel of daily life among the good and bad people of Maycomb County.

Speaking of conflicted characters, let's consider Atticus Finch for a minute. He's central to Scout's world in the novel. The book's title was once going to be Atticus. And he is a white man whose rock-steady character falls almost entirely on the generous, open-minded, and empathetic side of the scale. It's hard not to think of him as Gregory Peck after that sincere performance in the 1962 film of the novel. Atticus Finch has become an iconic hero to millions.

Yet, the character has also been criticized, rightly I think, for being a token liberal. That is, he's willing to fight the good fight for truth and equality in the courts, knowing full well that the system of which he is a supportive part is unlikely to offer up truth and justice for people like his client. Far from being a crusader, Finch is a lawyer who's just been handed a difficult assignment. This does not detract from his honourable intentions, nor take away from his extraordinary efforts to save Tom Robinson both before and after the trial's conclusion. Personally, I would prefer the character not be so philosophical about the trial's outcome, not accept the tragic end and the limits of his own role—I'd rather see him pushed by outrage into extralegal action or political protest—but I know this would not be realistic.

Atticus Finch is still of his time, place and profession. An earlier sketch of the lawyer in Lee's belated sequel/prequel Go Set a Watchman shows a segregationist Atticus Finch, indicating how much he evolved as a character in the writer's (or her editors') hands. That shouldn't be held against the Atticus Finch we come to know in To Kill a Mockingbird, but it does support the idea that the finished Finch did not arise from the forehead of Zeus as a perfect being. The character likewise must have had his struggles to get to his current position as a man, father, lawyer and prominent citizen.

Ambivalent nuances

Minor figures—like the judge, the newspaper editor, and Atticus's adult relations—also face struggles to do what is right without disrupting their standing in the status quo too drastically. Even the sheriff, a southern stereotype in other hands, is a moderately nuanced character, trying to be fair—at least among the whites—within the parameters of his position.

It helps that To Kill a Mockingbird navigates these ambivalences with great wordsmithing. Lee's insightful imagery and plain language capture scenes and characters poetically, better than any other American writer I can think of outside of F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby.

At times the observations are a little too mature for the six-year-old narrator but part of the excellence of the writing is in how it smooths out what might otherwise be a somewhat disjointed tale, bringing together a deceptively multiple number of perspectives, so we don't notice—or we don't care about—these discrepancies.

To Kill a Mockingbird may not satisfy some of us now who, after all these years of struggle, want a strongly worded anti-racist declaration once and for all. But it has spoken to and inspired millions of people to at least consider what it would be like, in Atticus Finch's words, to consider things from someone else's point of view, to "climb into his skin and walk around in it."

— Eric

Critique • Quotes