Thomas Hardy

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

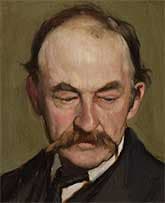

THOMAS HARDY portrait 1893 (W. Strang)

THOMAS HARDY portrait 1893 (W. Strang)Born

Stinsford, Dorset, England, 1840

Died

Dorchester, Dorset, England, 1928

Places lived

London; Dorset, England

Nationality

English

Publications

Novels, stories, poetry

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Literature

• Far from the Madding Crowd (1874)

• The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886)

• Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891)

• Jude the Obscure (1895)

Stories

• "The Three Strangers" (1883)

Poems

• "Neutral Tones" (1867)

• "The Darkling Thrush" (1900)

• "The Man He Killed" (1902)

British Literature

• Far from the Madding Crowd (1874)

• Return of the Native (1878)

• The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886)

• Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891)

• Jude the Obscure (1895)

The realist mistaken for a pessimist

Thomas Hardy made one of the wisest observations on writing:

The whole secret of fiction and the drama—in the constructional part—lies in the adjustment of things unusual to the things eternal and universal. The writer who knows exactly how exceptional and how non-exceptional his events should be made, possesses the key to the art.

The Life of Thomas Hardy by Florence Emily Hardy

Much talk of the "eternal" and "universal" in art is hyperbole. But if we take these words to mean having longer lasting importance than most things, Hardy is onto something. A writer may have to find the exceptional or novel to make a work interesting but, however much coincidence, horror, fantasy or other bizarre elements might be in a work, the author has to connect them with the mainstream of deep concerns that real people have. That is, if the writer wants to reach readers as Hardy has.

The standard academic line on Hardy is that his work shows the futile struggle of individuals against an indifferent force that rules the world and plays ironical tricks on frail humanity.

Rubbish. Hardy is just a realist. As he says of a poet in one of his short stories, "he was a pessimist in so far as that character applies to a man who looks at the worst contingencies as well as the best in the human condition".

Coincidences often drive his plots and certainly his characters often (but not always) suffer tragically. But the protagonist in any Hardy novel is more likely to be in conflict with his own very human obsessions, or struggling with rigid and unjust social codes, than against some faceless fate ruling the universe. His characters aren't railing against God but against followers of organized religion, not against the devil but against their own consciences.

Yes, he's depressed at times over who will win these battles. Who isn't?

Bad writer, great writer

Another thing that's said about Hardy, with more justification, is that he's a terrible writer of sentences and paragraphs.

Yet he's also a great writer of books. Somehow, shortly after you start plowing through his awkward constructions, you stop noticing it and are swept away with the story and characters. It shouldn't happen like this but it does.

Hardy can be classes with several other writers of the late Victorian and turn-of-the-century era—Joseph Conrad, Samuel Butler, perhaps Henry James—as transitional artists. They wrote intensely on issues of conscience, on struggling to escape past moral strictures to find, each in his way, a new understanding of human behaviour for the age to come. They developed writing styles that heralded the grittier, more realistic, more psychological work to come, but still had feet in the older grand tradition. Today's reader probably finds much to excite, much that is relevant, in their stories to place them squarely in the early twentieth century, but also hits those long, reflective passages on the ancient sentiments that relegate them to the bygone era of Dickens and Melville.

It's worth noting that, although we think of Hardy as a modern writer, working well into the third decade of the twentieth century, he was also a near-contemporary of Dickens. His first (unpublished) novel was written in 1867, three years before Dickens's death.

Thomas Hardy was born near Dorchester (which would become Casterbridge in his stories) in southern England. He planned to take holy orders but lost his faith in his twenties. After studying architecture in London, he returned to Dorchester where he did architectural work, while writing on the side. His first novel to be published was Desperate Remedies (1871), followed by the still-popular Under the Greenwood Tree (1872), which combines a love story with the travails of lovable village rustics.

But it was two novels later with Far from the Madding Crowd (1874) that Hardy made his name. This is a heart-rending story of forbidden love across social classes, betrayal and tragedy in a rural setting, and—surprise—with a happy ending. More or less.

Hardy's remaining most significant novels were The Return of the Native (1878); The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), a cleverly plotted emotional roller-coaster of a novel, often proclaimed his greatest work; The Woodlanders (1887), Hardy's personal favourite, another complex love story in a rural setting but with a tragic ending; Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891), a frank (for the times) account of the ruining of an innocent country girl, which was widely attacked for immorality: and Jude the Obscure (1896), about an earnest couple who try to resist the social conventions of the day.

Strange transformation

Jude the Obscure may have been Hardy's most pessimistic novel, and perhaps with good reason. His perceived flouting of morality in the work again roused condemnation by clergy, critics and even friends. In disgust, Hardy gave up novel writing altogether.

At which point one of the strangest transformations in literary history occurred. The great novelist became a great poet. From his first collection of Wessex Poems in 1898 to Winter Words published in his final year, he produced over 900 poems. You are most likely to find them today in editions of selected or collected works.

His poetry was not widely recognized in his lifetime but has since joined the canon of works that every schoolchild studies, most notably the short pieces "Great Things", "In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'", and "The Darkling Thrush". A three-volume blank-verse epic, The Dynasts, was published from 1904 to 1908.

Hardy wasn't a writer of fine or pretty verse. Rather he produced poetry in the language of everyday conversation. Often with a critical or ironic social perspective. And often restating his allegiance to the enduring truths of nature and the human heart. However, his verse today sounds stilted and old-fashioned. Although he considered his poetry more important than his prose, he made his point more effectively spread over the wider canvas of novels than in the condensed poetic form.

His short stories—at least the best of them—have fared better. Hardy often produced short fiction to make money in the periodical market and many of the tales were crafted for the sentimental demands of those readers. But the best stories are quite diverting even today. They aren't the sharp, finely honed short stories to be developed by younger authors in the twentieth century, but for short periods they can be as involving as his longer fiction.

His four major collections began with Wessex Tales in 1888 and ended with A Changed Man in 1913, but you're better off with a collection of selected stories. Look for a volume that includes his two best stories, in my opinion, "The Three Strangers" and the near-novella "The Distracted Preacher", which opened and closed Wessex Tales.

Odd trivia about Hardy: I haven't seen anyone else note this but Hardy seems hung up on women whose names begin with E. The ingénue in Casterbridge is Elizabeth-Jane. Other female leads in his works include Eustacia, Ella, Elfride, Bathsheba Everdene, Lizzy (short for Elizabeth?) and Ethelberta. And guess how the two women Hardy married were named? Emma and Florence Emily.

Coincidence?

— Eric

Critique • Works • Views and quotes