Joseph Conrad

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

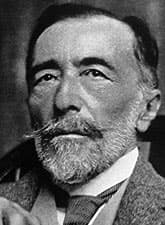

JOSEPH CONRAD, undated

JOSEPH CONRAD, undatedBorn

Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1857

Died

Bishopsbourne, Kent, England, 1924

Places lived

Ukraine, Poland, England

Nationality

Polish-British

Publications

Novels, stories, essays, poetry, plays, criticism, biography

Genres

Novels, stories, essays, memoirs

Writing language

English

Literature

• Lord Jim (1900)

• Heart of Darkness (1902)

• Nostromo (1904)

• The Secret Agent (1907)

• Under Western Eyes (1911)

Novels

• Lord Jim (1900)

• Nostromo (1904)

• The Secret Agent (1907)

• Under Western Eyes (1911)

Novellas

• Heart of Darkness (1902)

Stories

• "Youth" (1898)

• "The Secret Sharer" (1910)

• "The Tale" (1917)

British Literature

• Almayer's Folly (1895)

• Lord Jim (1900)

• Heart of Darkness (1902)

• Nostromo (1904)

• The Secret Agent (1907)

• Under Western Eyes (1911)

Adventure Fiction

• Heart of Darkness (1902)

Crime and Mystery

• The Secret Agent (1907)

Thrillers

• The Secret Agent (1907)

The great sea change

After having read so much Joseph Conrad—some forced upon me as a student, some for pleasure—I still find it hard to tell whether I like his writing. I gather other readers have a similar reaction. "Like" doesn't quite describe our appreciation of Conrad.

There are certainly Conrad stories and parts of Conrad novels you become completely immersed in, adventures you experience alongside his mysterious narrators every step of the way. Which seems to be what he aims for, why his writing is so detailed. With so many tricks of his characters' crafts. With so much telling minutiae of their daily lives. With every twist and turn of their tortured selves as they struggle through their latest physical or psychological crises. When it all works, it's completely absorbing.

But other times, the struggle is the reader's, having to push through dense prose, always majestically proper and readable, in hopes of getting to the expected moral payoff.

The payoff always comes.

Afterwards, you're always glad you've completed a Conrad work. You may not feel exultant as after the happy ending of a certain kind of popular novel. Nor pleasingly moved as after many another kind of story. But you sense you've acquired human experience that would have otherwise remained alien to you. You've learned something important and elusive about the human heart, or at least something about this world that the human heart has to deal with.

And then it's an effort to ramp up emotionally to take on another book. No one ever says, oh, goody, another Conrad to pass the time with.

Canon fodder

Part of the problem may be that Conrad has been so highly regarded as a Great Author for so long now. It can be hard to approach his writing without a feeling of obligation. This was the case even during Conrad's lifetime. By the time he had written the works considered masterpieces, he had been heralded by critics and other writers as one of the greats, but this hadn't gained him popularity with the reading public. It wasn't until Conrad was in his late fifties, that his lesser novels, like Chance (1913) and Victory (1915), started winning him wide acclaim.

In the century since, it hasn't helped that his works, especially the foreboding and psychologically intense novels of early middle age—Heart of Darkness (1899), Lord Jim (1900) and Nostromo (1904)—became standard teaching materials in high school and university literature classes, giving young people the impression Conrad is one of those old, old writers of refined, worthy material.

Sometimes The Secret Agent (1907) and Under Western Eyes (1911) are added to the canon, presented as precursors to modern espionage thrillers. But students soon learn these are early spy novels only in the sense that Crime and Punishment is sometimes called the first detective novel. Rather than page-turners, they are complexly structured studies in political and social psychology.

This image problem is too bad though, because Conrad may actually be read as our first modern writer. His most famous novels and stories were published well before the First World War, but he had tremendous impacts on postwar writers, who picked up on his unsentimental style, his roundabout narration, his insistence on precise language, and his deeply flawed heroes (anti-heroes in later parlance).

Many of those who developed the popular twentieth-century style—D.H. Lawrence, Ford Madox Ford, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Graham Greene—did so expressly by trying to write like Conrad.

They especially adopted his focus on surface details to suggest, rather than wallow in, emotional depths, Few however were able to successfully emulate his way of circling tighter and tighter around an embodied issue—usually a question of moral courage or personal integrity—until getting to the truth. To its dark heart, so to speak.

Romantic clichés?

Sometimes his approach is described with the shopworn metaphor of an onion but this is misleading. Conrad doesn't peel off layers to get to some inner insight. Rather, he swirls around an ever-intensifying surface. In Heart of Darkness the unnamed narrator describes the unusual way the character of Marlow tells a story:

The yarns of seamen have a direct simplicity, the whole meaning of which lies within the shell of a cracked nut. But Marlow was not typical (if his propensity to spin yarns be excepted), and to him the meaning of an episode was not inside like a kernel but outside, enveloping the tale which brought it out only as a glow brings out a haze, in the likeness of one of these misty halos that sometimes are made visible by the spectral illumination of moonshine.

This aptly represents one difference between Conrad's storytelling and that of many of his predecessors.

Not that he was universally admired and imitated by the moderns. Even some of those writers most influenced by him eschewed what seemed like an old-fashioned thickness of description. And some, notably Virginia Woolf and Vladimir Nabokov, considered the settings of his adventures—on the seas or in primitive European colonies—romantic clichés irrelevant to contemporary life.

Taking both the trendsetting and the criticized qualities of his work into account, Conrad is often categorized, along with Rudyard Kipling and perhaps with Thomas Hardy, as a link between the old and new literatures. A harbinger of the literature to come, rather than the fulfilment.

Yet we can still learn so much even today by reading Conrad as Conrad, a serious man with important, timeless stories to tell about us.

Lingering dread

Though he is best known for his novels, readers today may gain quickest entry into Conrad's world through his short and long stories.

His first great story, "An Outpost of Progress" shows the descent of two European traders into slave-dealing and violence in Africa and is often compared to Heart of Darkness. "Youth" (1898), first collected in the same volume as the novella Heart of Darkness, appears to be a straightforward tale of a young man's disaster-prone first sea venture. "Amy Foster" (1901) concerns a Polish sailor who is shipwrecked in England and falls in love with an local girl who never understands him. "The Secret Sharer" (1910) is another story of a moral dilemma at sea, when a ship's captain must decide whether to protect a seaman who killed another. "The Inn of the Two Witches" (1915) is an Edgar Allen Poe-style tale of a night spent in a deadly house, a story that may come as a revelation to those who think of Conrad as working in only one genre or milieu.

Once you ease into Conrad, overcoming any lingering dread of the Great and Worthy Author, you'll have years of great reading and re-reading ahead of you. You may not enjoy it, whatever enjoying a book means to you, but you'll feel better for it in the long run.

I'm sorry if that makes Conrad sound like castor oil. Most of his writing goes down more easily than I've probably made it sound. His best work really is great stuff, with a lowercase G.

— Eric

Critique • Works • Views and quotes