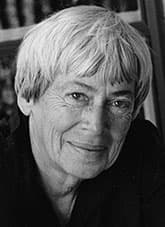

Ursula K. Le Guin

Critique • Works

Born

Berkeley, California, U.S., 1929

Died

Portland, Oregon, U.S.

Places lived

Steventon, Hampshire, England; Winchester, Hampshire

Nationality

English

Publications

Novels, novellas, stories, essays, poetry, storybooks, criticism

Genres

Science fiction, fantasy, children's literature

Writing language

English

Literature

• The Earthsea Cycle (1968–2001)

• The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

• The Dispossessed (1974)

Novels

• A Wizard of Earthsea (1968)

• The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

• The Dispossessed (1974)

Novel Series

• The Hainish Cycle (1964–2000)

• The Earthsea Cycle (1968–2001)

Stories

• "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" (1973)

• "Buffalo Girls, Won't You Come Out Tonight" (1987)

Story Collections

• The Wind's Twelve Quarters (1975)

American Literature

• The Earthsea Cycle (1968–2001)

• The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

• The Dispossessed (1974)

• The Wind's Twelve Quarters (1975)

Adventure Fiction

• The Earthsea Cycle (1968–2001)

Fantasy Literature

• A Wizard of Earthsea (1968)

Fantasy Series

• The Earthsea Cycle (1968–2001)

Fantasy Stories

• "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" (1973)

• "Buffalo Girls, Won't You Come Out Tonight" (1987)

Science Fiction

• The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

• The Dispossessed (1974)

Science Fiction Series

• The Hainish Cycle (1964–2000)

Science Fiction Stories

• "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" (1973)

So human, we aliens

The growing respectability since the 1960s of what is loosely called science fiction can be attributed to Ursula Kroeber Le Guin as much as to anyone. Crossover acceptance of Le Guin's work—the recognition of it being good, even great, literature—brought many mainstream readers to what had formerly been considered a narrow genre appealing to young males, concerning space battles and bug-eyed monsters.

Her themes are profoundly human, saying more about us here and now than about alien beings in an imagined future.

The reaction in the SF community to her wider acceptance has sometimes been to complain that she does not write genuine science fiction. Her stories often involve time and space travel to other worlds, but she does not deal with the science, it is said.

The SF trappings are there just to bring her characters into novel situations where her focus is on their relationships with each other and, most importantly, their relationships with their environments and societies. Religion, philosophy, psychoanalysis and anthropology are woven throughout these relationships.

Okay, so don't call her a science-fiction writer. Call her a writer of speculative fiction, which could also include her fantasy tales. Or come up with a new term to describe the Le Guin hybrid. But, by any name, her writing touches a lot of people.

Expanding humanity

Sometimes her work is similar to that of J.G. Ballard (The Crystal World, Empire of the Sun) in that protagonists we can identify with are thrown into alien environs, which leads them (brazed us) to reconsider assumptions and embark on inward journeys of discovery.

Ballard's characters come to accept the indifferent or hostile otherness of reality, however—while Le Guin's characters journey to expand their own inherent humanity.

Born Ursula Kroeber in Berkley, California, Le Guin had a pioneering anthropologist father and a noted-author mother. She started off writing poetry and realistic novels (unpublished) before turning to science fiction and fantasy.

Many of her early SF stories, novellas and novels take place in our future galaxy which is revealed to have been seeded by people from the planet Hain, creating worlds of great biological and social diversity, but with a human stock of common origin.

A peaceful league of these worlds develops through the centuries in Le Guin's works. The first full-scale novel Rocannon's World (1966) features an ethnographer marooned on a primitive world on which mental telepathy ("mindspeech") is discovered. Planet of Exile (1966) concerns an Earthling colony on a planet whose native inhabitants they treat with disdain. City of Illusions (1967) takes place on Earth ruled by invaders who use a perversion of mindspeech, called "mindlying".

Le Guin's popular and critical breakthrough came with the fourth novel in the series, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969). This novel, which can be appreciated without knowledge of the preceding works, follows the exploits of an emissary from the Hainish league of planets to a pre-space world. The unusual features of the planet Gethen are that it is very cold and its inhabitants are androgynous—neither entirely male nor female—except during several days per month when they are in heat and take on the characteristics of whichever sex complements their partner at the time. The novel won the two highest awards for science fiction, the Hugo and the Nebula.

The Left Hand of Darkness was followed by two Hainish novellas, Vaster than Empires and More Slow (1971) set on a planet of sentient plants and The Word for World is Forest (1972) about the exploitation and liberation struggle of the natives of a wooded world, an obvious (at the time) Vietnam analogy. The latter appears in Volume 1 of Again, Dangerous Visions, the celebrated anthology edited by Harlan Ellison, and won another Hugo. It was also published separately later.

The Nebula-winning story "The Day before the Revolution" (1974) introduces an anarchist society that would be featured in the last major Hainish novel, The Dispossessed (1974). That novel repeated the success of The Left Hand of Darkness by winning both the Hugo and Nebula but is regarded as one of her most difficult works.

Subtitled An Ambiguous Utopia, The Dispossessed is her most politically sophisticated novel—maybe the most politically astute novel in all science fiction (and I'm counting Nineteen-Eighty-Four). It takes us back to an earlier time in the Hainish cycle, to a physicist who discovers a new mathematics, which will lead to a method of instantaneous communication of widespread use in the interstellar world. But the bulk of the novel pits three types of social organization against each other—capitalist, Soviet-style socialist, and anarcho-syndicalist—with the renegade scientist investigating the successes and failures of each in providing individual and collective fulfilment.

Beloved fantasy series

One of Le Guin's most popular works in this period was a non-Hainish novel, The Lathe of Heaven (1971). Concerning a man who can dream alternative realities into existence, it's been compared to the reality-twisting work of Philip K. Dick. It has twice been made into television movies: the first in 1980 for PBS has developed a cult following and remains more highly regarded than the 2002 remake on A&E.

Most other non-Hainish short stories up to the mid-1970s can be found in the collection, The Wind's Twelve Quarters (1975).

Le Guin's most-beloved work, however, may be the Earthsea fantasy series written almost contemporaneously with the Hainish tales. It starts with A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) in which a young sorcerer's apprentice, Ged, sets out on his career as a magician in a world of islands and eventually faces a powerful evil force, both internal and external. The second entry in the series, The Tombs of Atuan (1971), takes Ged into another adventure but is told mainly from the point of view of a new character, the young priestess Arha. Taking Ged through his mature and last years is The Farthest Shore (1972), which won a National Book Award. Years later Le Guin added Tehanu: The Last Book of Earthsea (1990), focusing on the power of women and winning one more Nebula, and then—belying the previous title—another book, Tales from Earthsea (2001). And most recently a fifth Earthsea novel has appeared: The Other Wind, which continues the Tehanu story.

Among Le Guin's prodigious output over the years has been her acclaimed story "Buffalo Gals, Won't You Come Out Tonight?", which won yet another Hugo and was turned into a graphic novel of the same title in 1994.

Always Coming Home (1985) is an experimental collage of poetry, stories, drawings, recipes and other documents, and was originally distributed with a cassette of music, all providing an immersive experience of a matriarchal society in a future California.

Le Guin has also published numerous volumes of essays, literary criticism, interviews, poetry and children's books, in addition to editing story collections. One of her most interesting and provocative nonfiction books is The Language of Night (1979, revised 1989), containing twenty-four essays on feminism, fantasy and the craft of writing science fiction.

— Eric

Critique • Works