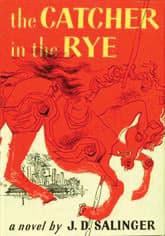

The Catcher in the Rye

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1951

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 76,000 words

Some get caught and some don't

Few novels divide readers as The Catcher in the Rye does.

This may sound like a bizarre thing to say, since J.D. Salinger's novel has been wildly popular since it came out in 1951. It's been lauded as changing the course of post-Second World War writing—at least American writing—as much as Ernest Hemingway's work did in the inter-war period. Tens of millions of copies of Catcher have been sold and hundreds of thousands more every year. Globally acclaimed, it would appear.

Yet, from my discussions with my fellow great unwashed masses, I've learned that a lot of people just don't get it.

And it's not their fault. Nor the fault of the author.

Those who don't get The Catcher in the Rye are not making the kind of complaint you hear from folks about James Joyce's Ulysses or Tolstoy's War and Peace or even older classics like any of Dickens. Catcher is not a difficult modernist read, nor a dauntingly heavy book, nor a novel full of archaically convoluted descriptions and allusions that only literary or academic types could fathom. Rather, it's a relatively short, colloquial, breezy read that anyone can follow.

In a way, we can follow it too easily. Nothing much seems to happen. We go through a few days in the life of a spoiled rich kid who is expelled from prep school in New York and wanders around town criticizing everyone, "phonies" all of them, and feeling sorry for himself. Every now and then he gets sentimental about someone—a kindly teacher, an old girlfriend, his younger sister—but is quickly disillusioned. And in the end, for all his supposed rebellion, he is poised to take up his role again as a son of the privileged class.

You've got a point

There seems nothing further to get. If you come to the novel having heard it's a great work of social criticism, you're bound to be disappointed. How profound or incisive can the interior carping of a self-centred twerp be?

To such disappointed readers, I can only say, "Yes, you've got a point." There are reasons The Catcher in the Rye doesn't speak to you. Maybe it's not destined to become one of the great universal classics of American lit up there with Huckleberry Finn. In fact, I suspect the legions of its dismissers will grow the further we get from the zeitgeist of the mid-to-late twentieth century.

But let's look at why, at least in its own era, it's been such a sensation.

Of primary importance is its style and what scholars refer to as its voice. Right from the first line, Salinger serves notice this story is not going to be presented like anything its readers had ever read before. The line dispensing with "all that David Copperfield kind of crap" heralds both a new kind of story structure (specifically not a Dickens-style coming-of-age story) and a new kind of language to tell the story. Lots of writers had used profane speech before, but few had made this an entire novel. Salinger sustains the profane, adolescent tone of Holden Caulfield as narrator through almost the entire novel, without a false note struck in more than two hundred pages.

Today, with generations of scribes having copied this trick, it's hard to realize what an astounding feat this was back then.

Caulfield's verbal tics have provided material for parodies: tagging sentences with vague phrases like "and all" and "if you want to know the truth", overusing "phonies", putting "old" before people's names, spicing it up with weak expletives like "goddam" and "for God's sake"—and everything "driving me crazy". Salinger is easily satirized for lines like "People never think anything is anything really. I'm getting goddam sick of it." The kind of lines you probably learn in writing school to rewrite with more concrete imagery. Vague but meaningful to anyone on the same wavelength as Holden.

They put me in mind of some of the purposefully inarticulate lyrics of John Lennon as in Strawberry Fields Forever years later: "Always know, sometimes think it's me / But you know I know when it's a dream / I think a no I mean a yes / But it's all wrong / That is, I think I disagree." (Although Lennon's tragic connection with The Catcher in the Rye is another painful matter entirely.)

Ripped from their minds

Some critics have complained about the novel's unimaginative, often flat sentences, as if they show the author's a bad writer. They're missing the point. Of course, J.D. Salinger could have written the story more creatively—but Holden Caulfield couldn't. Salinger shows incredible discipline really in sticking to the kid's voice, even when he's inarticulate.

And then when the kid does show tremendous sensitivity and insight, expressed in the vulgar language that more refined writers of sensitivity and insight don't use...well, it's magical. It strikes the reader, or at least a certain kind of reader, as all the more real.

I think this is why The Catcher in the Rye has caught the affection of so many rebellious young people, including some famously unhinged killers. Many novels have critiqued modern society and its denizens, but few, if any, in the kind of language that makes those readers feel the thoughts are ripped from their own minds.

But I think this also explains why not everyone feels this way about The Catcher in the Rye. If they are not the kinds of thoughts you already have and if Caulfield's voice does not resemble yours to some extent, then the language can leave you unimpressed. Or it impresses you in the way that someone doing accents can impress you without moving you.

Of course, the novel's actual critiques of people and upper middle-class urban life are also important to the novel's reception, especially by the cynical. Salinger is a deeply cynical writer. It's been suggested in some quarters that Catcher is really a novel of post-traumatic stress, that Caulfield experiences school and New York as Salinger had experienced the war, wandering both battlefields in shock, uncomprehendingly, in need of help to pull themselves together again and continue as soldiers/citizens.

Interesting idea, but I find Caulfield's caustic take on his arena of action much more juvenile than might be expected of a soldier. Norman Mailer (who wrote a real war novel) called Salinger the "greatest mind ever to stay in prep school." The first time I heard this I thought it was just a bitchy comment from a rival writer but it's grown on me as a general explanation of at least The Catcher in the Rye.

This is not necessarily a criticism. Salinger creates Caulfield as a prep school rebel. The perspective in the novel is that of the character, who has never got beyond this teenage world view. Salinger made a masterful work of it. Which, by no means, is to imply anyone should take it—or less to act on it—as a mature statement of the way the world is.

I expect, as time goes by, people may be able to see this more clearly and let the novel take its place as a minor classic of its time that had an outsize effect on literature to come.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes