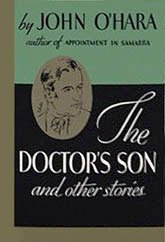

The Doctor's Son and Other Stories

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1935

Literature form

Story collection

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

• Stories (for "The Doctor's Son" and "Over the River and Through the Wood")

The great theme of ordinary life

The short story "The Doctor's Son" could alone carry John O'Hara's reputation as a story writer.

Conversely the collection in which it appears, his first book of short stories, is not enough to give justice to his reputation.

What justifies his reputation as one of the greatest American story writers of any time is his entire output of story collections, published from 1935 until after his death in 1970.

But we have to pick one item for our "Greatest" list. So it might as well be the compendium of thirty-seven vignettes, The Doctor's Son and Other Stories, which first established O'Hara's name with the wider public who hadn't already discovered his work in The New Yorker or other high-toned magazines.

You won't easily find The Doctor's Son and Other Stories today. You're more likely to read the stories in books that select a couple dozen stories from his hundreds of published stories.

My favourite of these is The O'Hara Generation, published near the end of the author's lifetime and offering the widest selection of stories, covering all periods of his career equally from the 1930s to 1966. In case you cannot find this volume, the readily available Selected Short Stories of John O'Hara of 2003 is a passable introduction. Most other selected editions show too strong a bias for his earlier work, giving the erroneous impression he produced little of value in the short form after the 1940s.

Common to most O'Hara story collections are the early works "The Doctor's Son" and "Over the River and Through the Wood". The first is narrated by a teenager who helps a young medical man fill in for the youth's sick father, administering to the culturally diverse inhabitants of the rural community. In thirty-odd pages, a novel's worth of characters and situations are effortlessly presented. O'Hara appears at this time a completely naturalistic writer with a keen ear for dialogue and an equal eye for the telling social detail. The story is reminiscent in tone of the famous Hemingway story of a doctor's son being brought face to face with adult reality. But O'Hara is less ironic, more accepting of all his characters.

"Over the River and Through the Wood" may also have a Hemingway connection as I've wondered whether the older writer was influenced into calling one of his novels Across the River and into the Trees. But O'Hara's work is no war tale. It's a quiet little story—barely seven pages long—about an elderly man who takes a disastrous trip with younger people.

Other stories in that first Doctor's Son collection are little more than vignettes by length—three or four pages of conversation. But they carry emotional impact belying their seemingly underwritten style.

The way we talk

O'Hara's follow-up collections continue developing his distinctively conversational style. Interestingly though, it really cannot be said that his dialogue sparkles. It is nearly impossible to pick out incredibly witty comments for quoting from O'Hara's characters. Rather, his dialogue is great because it is so ordinary. It's the way people—Americans mostly—actually talk. Yet the dialogue does so much work. O'Hara scarcely has to say who's talking, as it's obvious. Or what's happening. Or what the characters are thinking. It's all so clear, same as when you're talking with your best friend about things that mean a lot to both of you. Or when you're talking trivially but both thinking of more important matters.

And, despite complaints of O'Hara obsessing over high-society, in reality he applies his storytelling skills to a wide variety of milieus, ranging through the foibles of artists, professional families, hotel habitués, diner denizens, private schoolboys, gamblers, and figures in the theatrical and film worlds. If anything, he seems most at home with the middle-class citizenry, with their everyday concerns, especially their male-female relationship issues.

Among the best of this period are "The Hotel Kid", "The Public Career of Mr. Seymour Harrisburg", "Price's Always Open", "No Mistakes", "Summer's Day", "The Next-to-Last Dance of the Season", "Where's the Game?", "The Decision" and "Drawing Room B".

After a literary spat with The New Yorker, O'Hara took a break from story publishing in the 1950s and when he came back his story writing had begun to change. The usual criticism is that he had become less disciplined as a writer, knocking out stories that rambled to excessive length without ever finding focus. It is true that it seems his willingness to let dialogue lead him anywhere the characters felt like sometimes resulted in works longer and more verbose his earlier, tightly controlled pieces. But does that really matter, as long as they still hold reader interest? In his later period, he also produced some small masterpieces that I hold could not have come from the younger O'Hara.

A case in point is the 1961 story "Mrs. Stratton of Oak Knoll", which is seldom anthologized and may represent the first full flowering of his later style. At times it reads like a truncated novel. It breaks the unity of the classical short story, moving around the point of view. It starts with a comfortably established artist and his wife discussing the mysterious goings-on at the home of the rich lady across the street and moving on to present extended conversations between shifting twosomes from among the story's handful of characters, including with the old lady. In the course of all this, several stories-within-the-story are introduced and resolved. this sounds like a mess but it actually holds together very well. It's engaging from beginning to end.

After this, most of O'Hara's stories—those that can be found—are similarly lengthy and involved, and don't always resolve cleanly. But this may not be considered failure. You can read them as too long, failed short stories, or you can read them with great rewards as condensed novellas.

In this category are such gems as "You Can Always Tell Newark", "Pat Collins", "The Hardware Man", "Andrea" and "Fatimas and Kisses".

O'Hara in this latter period may be seen as creating a new category of writing. It's a dramatic form in which real folks address their ordinary concerns in their everyday language, with results similar to those in real life. We learn a bit, we lose a bit, but we're wiser for the experience. Especially when a master story writer distils it for us.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes