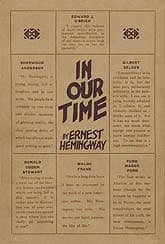

In Our Time

Critique • Other views • Quotes

First commercial edition, 1925

First commercial edition, 1925First publication

1924, Paris, vignettes appearing in in our time

First complete publication

1925, New York

Literature form

Stories, vignettes

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 47,500 words

See the serious writing student

It may seem perverse to pick In Our Time as Ernest Hemingway's greatest story collection because many individual stories in later collections have become more familiar—and are arguably more accomplished than these earlier tales.

However, Hemingway's early stories set a new standard for story-writing. Strangely perhaps to our eyes and ears, these stories were shocking when they hit the public in 1925. Shocking because they were written so differently than anything that had appeared before.

To some, they just seemed quirky. Juxtaposing the horrors of war and the mundaneness that those who live through it strive for. White-hot intensity without theatrics. Understated to the point of somnambulism at times but with heavy emotional undercurrent. For many this was writing for the new world after the First World War, the birth of genuinely twentieth-century literature.

And the stories of In Our Time have proven themselves to be such, even if none of them on their own have stood out as blockbusters. Unlike some later Hemingway stories, they haven't been seen as suitable for movie treatment. But they are uniformly excellent.

And they hang together well. In fact Hemingway gives each story a chapter number as if together they form a continuing narrative.

Conflicted simplicity

In these stories we can see the serious young student of writing reach a mature level of assurance in developing his own style, a style that was unlike any before. Today when we read these stories we may not be as aware of how revolutionary they were, since the direct language and the understated sardonic attitude have become part of the mainstream, adopted to some degree by almost every popular writer since then. Yet, in our day, the stories of In Our Time are still read with a conflicted simplicity that is still fresh.

The book introduces Nick Adams, a character apparently standing in for Hemingway, who will appear in dozens of his stories over the years. We see him at various points of his upbringing and early adult life in rural and backwoods America. The naturalistic stories are interspersed by contrasting vignettes from the war, usually told in the first person.

But it is the finely honed matter-of-fact style that makes the emotional undercurrent so forceful—whether the story concerns Nick's relationship with his doctor father, his being down and out riding the rails, or a horrific incident during the war. Here is one of the latter vignettes in its entirety:

They shot the six cabinet ministers at half-past six in the morning against the wall of a hospital. There were pools of water in the courtyard. There were wet dead leaves on the paving of the courtyard. It rained hard. All the shutters of the hospital were nailed shut. One of the ministers was sick with typhoid. Two soldiers carried him downstairs and out into the rain. They tried to hold him up against the wall but he sat down in a puddle of water. The other five stood very quietly against the wall. Finally the officer told the soldiers it was no good trying to make him stand up. When they fired the first volley he was down in the water with his head on his knees.

Not a word too much or too little. Hemingway knows exactly what to leave in and take out.

The strangest story

The collection ends with one of the strangest stories you'll likely read.

In "The Big Two-Hearted River," printed in two parts, Nick returns to an old fishing haunt and goes fishing.

That's it. No other characters. No dialogue. No obvious conflict with man, nature or oneself. Just a man methodically going about his recreation with focused skill and attention to detail.

Yet with uncanny submerged emotion contrasting with the supposed big-heartedness of the river.

It's disquieting. Has he just returned from the war? Is he recuperating from injuries? From trauma? Is he trying to recover the past? Is he escaping the past? Or is it just another uneventful story about fishing?

— Eric

Critique • Other views • Quotes