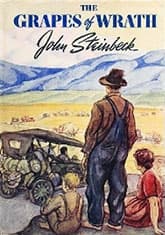

The Grapes of Wrath

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1939

Literature form

Novel

Genre

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 176,000 words

Red harvest

The Grapes of Wrath is John Steinbeck's most controversial work, seeming to advocate a socialist revolution to end the misery of the dispossessed folks during the dirty nineteen-thirties. It can only be this apparent political stance that has kept everyone from unanimously recognizing the novel as one of the most powerfully and brilliantly written in American literature.

Many have recognized it as such over the years though and The Grapes of Wrath has passed nearly into legend. The novel appears on most lists of the great books of the twentieth century. It's been adapted for a popular and relatively faithful movie starring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad, as well as for a stage play that has been presented on television. It's the subject of songs by Woody Guthrie and Bruce Springsteen.

The novel itself follows an Oklahoma sharecropping family as they are forced off their land by dust and by rapacious banks and they join the flood of displaced humanity across the American Southwest to promised fruit-picking jobs in California. But in the land of plenty the Joads and their fellow travellers find even greater misery. They're exploited by large landowners to the limits of their existence and beyond. They're attacked by police and vigilantes. Their families break up. They get thrown in jail. They starve. They are prevented from finding shelter from the elements. They bury their old folks. And they bury their children.

This synopsis doesn't do justice to the depth of their suffering. And yet—somehow—the novel is not despairing.

The Joads' desperate straits are presented in the context of the greater events taking place in this part of the world at this time, usually given in chapters alternating with the Joad saga. And always there is the trust that eventually the good folks—"us people", in Ma Joad's words—will band together to set things right. A great change is coming. We don't see it in their immediate experience, but the novel ends with a small incident that must rank as one of the most affecting examples of humans helping each other in all literature.

And this is what makes The Grapes of Wrath the perfect political novel. We never hear from politicians of any stripe, nor see them in action. The people keep getting warned of "red agitators", especially when they raise the slightest objection to their treatment, but we never meet any communist activists.

The novel focuses on the ordinary folks themselves who strive mightily to protect themselves and come to think maybe they are "reds". We never read any leftish theory or hear any class warfare rhetoric, but we follow the progress of the people themselves reaching their own conclusions about what is happening to them and the need to work collectively to change their fate.

Creeping sentimentality

On every page can be found gems of creative expression. Whether it's a turn of phrase or paragraph that sheds light on a social situation. Or a quirky bit of colloquial dialogue. Or incisive insight into the human heart. Or a joke. Or a small gesture that speaks volumes about character.

If Steinbeck's writing in The Grapes of Wrath can be criticized for anything, it might be for a sentimentality that creeps in between the direct exchanges of simple people undergoing horrendous experiences. Sometimes "us people" are just a little too wise, too articulate and too noble to be real. Certainly, Steinbeck is clear-eyed about the jealousies, greed and ignorant notions that rise up among the people and threaten keep them from advancing together, but he is also determined that we understand the greater unity and good will that lie beneath.

Perhaps he overdoes it at times. But can't we let him have that? With all the propaganda—all the art and literature!—that keeps telling us how evil and petty people are, can't we let him go a little overboard in the other direction? To counter all that negativity, can't we let him drill home the more positive view that people are not really any one thing—neither good nor bad, neither sinful nor righteous—except as human society makes them?

Even late in life, despite writing some increasingly pessimistic works, Steinbeck held onto his progressive view of humanity.

"I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectability of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature," he said in his 1962 Nobel acceptance speech. The Grapes of Wrath may be his greatest exploration of human potential, finding it in the darkest moments of our social history.

Which makes for a great novel, whether or not you agree with the characters' political awakening.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies