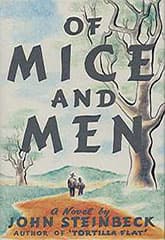

Of Mice and Men

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1937

Literature form

Novella

Genre

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 34,500 words

Small but punchy

It has always seemed like the perfect American novella. A poignant and disturbing story told effortlessly, of simple folks on the fringe of society who turn out to be quite complex.

But read Of Mice and Men a second or third time and its clever structure becomes more apparent. John Steinbeck's greatest work before The Grapes of Wrath is a classically concise piece of theatre.

Or cinema. Start with the beginning shot: the clearing by the stream where animals come to rest or drink. Coming in from stage right, are two men, whose names we learn first from their dialogue and whose characteristics and characters are built in short order from their speech and interaction. We quickly learn their recent pasts.

A scene or two later, the large, lumbering Lennie Small and the canny, caring George Milton appear at the ranch to take their place among other itinerant farm workers. In short order, the secondary characters are paraded through, all quickly revealing their strengths and (mainly) weaknesses, their sensitivities and cruelties—their confusions. And when the boss's belligerent young son and the son's provocative wife appear, you can practically hear the Greek chorus prophesying doom at their hands.

It all works out as fated, as several characters predict and later remind us they'd predicted. Which is to say, it doesn't work out at all for the main characters. But, even when we are sure how it must end, we are drawn through it, mesmerized by the men's hopes, lulled by the continual repetition of evocative phrases, which make a fable of their dreams and become a near-religious liturgy, an old trick of dramatic recitation going back to ancient times.

And then the concluding scene with a typical Steinbeck twist. No, not typical, because Steinbeck is a genius at completing works and never uses the same emotional ruse twice. Of Mice and Men's final act of killing, accomplished with an understated mixture of practicality and pent-up tenderness, stands with the breastfeeding image of The Grapes of Wrath as one of the great humanistic endings that can stay in your mind forever.

Deceptively relaxed

It has all taken place within a day a or two. Yet within each of the economically built scenes, the human drama has evolved naturally through dialogue and monologue, and through the apparently casual interplay of personalities. So many of the book's memorable lines are direct quotes from the characters. the story even ends on dialogue.

Throughout Of Mice and Men the pace is deceptively relaxed, allowing the ambiguities of several of the secondary, as well as the primary characters, to come out—most notably with Crooks, the derided but surprisingly educated black worker known as the "stable buck"—but the drama is quickly heightened without a misplaced or extra word.

It takes a great deal of concentrated effort to get across so much subtlety in ordinary narration without sounding either overly literary on one hand or too folksy on the other.

Steinbeck's accomplishment here, as elsewhere, is to present high theatre as everyday reportage.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies