The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

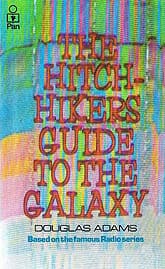

First edition

First edition• The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, 1979

• The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, 1980

• Life, the Universe and Everything, 1982

• So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, 1984

• Mostly Harmless, 1992

First publication of novels

1979—1992

Literature forms

Novels

Genres

Literary, science fiction, humour

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

First novel approx. 46,500 words

It's a funny, old universe

To get an idea of what the Hitchhiker's Trilogy is like, you have only to read the titles of the five novels that comprise it: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy; The Restaurant at the End of the Universe; Life, the Universe and Everything; So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish; and Mostly Harmless.

Bizarre. Cosmic. Ironic. Plain funny.

That this "trilogy" consists of five novels is enough to break up some of us.

Read any of the first lines (see Quotes) and you'll know you're in for a mind-boggling, crazy-philosophical ride.

Or check some of the popular lines from the stories (hundreds more quoted all over the Internet and stolen by numerous other writers). You'll sense how these books became an entertainment phenomenon.

Or read the opening pages of the first novel, also known as The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Our common-man hero Arthur Dent is protesting the demolition of his home to make way for a highway when an alien ship suddenly announces it is destroying the Earth to make way for a galactic bypass. Dent escapes the planet's demise thanks to his best friend Ford Prefect, who turns out to be an extraterrestrial reporter for the Hitchhiker's Guide of the title. With the help of a lot of beer quickly quaffed and a bag of peanuts, they catch a ride on the alien craft, piloted by a lovesick Vogon who threatens to read them his poetry but instead throws them into space. And this is just he beginning.

Answer to the ultimate question

What follows is a time-, space- and mind-warping odyssey around the universe, involving a two-headed, former-president-of-the-galaxy-turned-spaceship-thief (the infamous Zaphod Beeblebrox), a depressed robot, a planet-sized computer which works out the answer to the ultimate question of life leaving only the small matter of the question itself to be determined, the end of the universe packaged as a floor show for time-travelling diners, and more.

Alice in Wonderland upgraded to Arthur in the Wonderverse. Doctor Who performed by the Marx Brothers. The apocalypse as told by the comedy team of Woody Allen and Werner Heisenberg.

But is it any good? That is, is Hitchhiker's Guide good literature? Does it have any depth? Is it of enduring value or is it just a passing fancy of popular culture?

I could say, "Who cares?" The stories have diverted and challenged us in the last years of the twentieth century and early years of the twenty-first to make them "great literature" right now, whatever posterity decides.

But somehow that isn't enough for many of us. We want something more lasting from what we invest our reading time in. Sure, we have our junk reading too—just as we have our TV-watching time and our silly movie escapes—but we want to feel that some of what we read is important beyond momentary diversion. Is Hitchhiker's Guide good beyond being a comedy act or a pop philosophy lesson in print?

Some of the cultural references have already become dated. There's a running joke, for example, about a new branch of mathematics based on the incomprehensibility of calculations on restaurant checks. Now that most checks are computer produced rather than scrawls by waiters, the effect of this conceit is somewhat diluted. And there are the references to pop stars of the 1970s. Or the cliché of messy New York City prior to the 1990s cleanup.

But this isn't fatal. Great works as old as Dante's Inferno have often been loaded with references to people and events that only contemporaries could understand without footnotes.

Aging genius

How about the ideas though—have they aged? Yes, it's no longer shocking to read that the destruction of the earth could be due to a bureaucratic foul-up. That idea's been milked by black-humoured films and fiction. The juxtaposition of profound cosmic questions with trivial human obsessions like digital watches is no longer a sign of comic ingenuity, as comedians from Steven Wright to Monty Python have made careers from it.

But part of this aging is due to the very success of Adams, along with other writers and performers of the past several decades. This ironical, topsy-turvy approach has become a dominant strain in our culture. So much so that the once freshly subversive concepts now appear stale. Also, many of the highlights of the Hitchhiker's Guide books have become widely known even among those who haven't read them. Ask anyone of a certain age the significance to the universe of the number forty-two.

Even by the end of the second novel in the series there's evidence of the act wearing a bit thin. The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and The Restaurant at the End of the Universe together make up Adams's original story. The first is especially startling and exhilarating. The second book couldn't possibly top the surprises of the first, but it comes close. Its conclusion leaves lots of loose ends but they don't matter—haven't we found out the whole universe is a conglomeration of unintended results and loose ends?—and it's emotionally satisfying. Dent never recovers the Earth as he knew it and no one ever solves the great mysteries posed by life, but a certain acceptance is attained.

But then Adams has to go and try to make the story into a trilogy with Life, the Universe and Everything. He attempts to up the ante, to wrap up the mysteries of the first two books in an even bigger, universal conspiracy, worthy of the title. (All the titles in the series are taken from phrases presented in the first book—as is even one of Adams's non-Hitchhiker's titles—as if there is a continual attempt to live up to that great first work.) The story in the third novel involves probability and illusion on a wider scale, and frankly none of it makes much sense. Not that we want sense in a normal kind of way but at least in the way of the first two crazy books, in which we could share Arthur Dent's introduction to the insanity. In this one we're on our own, adrift in the incomprehensible universe. It's all very ponderous and dull.

It's a problem with works that undercut our assumptions. If they keep on eventually the reader has nothing left to stand on and the writer's world starts appearing just arbitrary. But if they pull back, they run the risk of seeming to cop out after bold beginnings.

Well, in the fourth book appended to the initial trilogy, Adams pulls back. And it works. Although it fails to please all his fans.

Sweet tale

In So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, Arthur is back on modern Earth which was never destroyed after all—or was it? A female character who hadn't been seen since page one of the first book when she was killed in the destruction of Earth is back—we think. Adams produces a fantastic love story between these two people who seem to have come from different parallel realities. The explanation of the seeming contradictions is hinted at but not delved into. The other bizarre characters from the first three books make appearances and there's some galactic funny-business going on as usual, and Arthur and his lady do some sleuthing into what happened back when the world was not destroyed, but this is mainly a sweet tale. Much of Adams already seems to me like Dick-lite (as in Philip K. Dick), but this is the story that most approximates Dick's entanglement of intellect and emotion, complete with shifting focus and unresolved issues. A mature but uneven work.

The last book, Almost Harmless, is somewhere in-between. It picks up the mixed alternative realities story some years later after Arthur's lover has vanished in a time-space anomaly and he looks for a new planet to live on. Meanwhile Ford Prefect fights his publisher, the Hitchhiker's Guide, which has been taken over by a corporation whose new marketing plan is to sell only one copy of the guide but to sell it billions of times over in alternative universes. A large part of the plot also concerns Tricia McMillan, part of the space-faring team in the first three books, who made different choices in this reality. Characters from different realities intermingle. I liked this book, was stimulated by it, but some Adams fans call it his worst ever. In any case, it nicely ties the story together, bringing the whole series full circle. By the somewhat depressing end, it is clear the Hitchhiker's Guide narrative is played out. Adams was apparently working on another sequel when he died, but I'm happy to let it go at this point.

If you're interested in this series, my recommendation is to get one of those all-in-one "trilogy" compendiums comprised of the five novels. Some even include "Young Zaphod Plays It Safe" (1986), the only short story Adams ever wrote in the Hitchhiker's world, but it's not necessary. Read through the not-quite-stellar sections to get to the final, well-played resolution. Afterwards you'll forget the rough spots and look back at the weird and wonderful trip it's been.

If you're unsure this kind of material is for you but are curious, get the first two novels at least. That'll give you enough of the basic Hitchhiker's Guide lore to see what all the fuss is about.

And to suddenly understand dozens of everyday cultural references that previously went over your head.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies