The Killers

Critique • Quotes

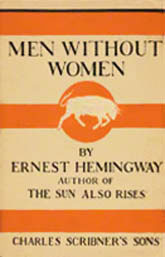

Collection first edition, 1927

Collection first edition, 1927First publication

In Scribner's Magazine, 1927

First booki publication

In Men Without Women, 1927

Literary form

Story

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 3,500 words

But you think about it nonetheless

When they made a movie of "The Killers" in 1946 they spent only about fifteen minutes telling Ernest Hemingway's entire story from two decades earlier. The rest of the screen time they devoted to fleshing out the narrative, showing at great length how the situation depicted in the story came about, namely how the killers' target got himself into that predicament.

Which is so unnecessary, as this is already implied in Hemingway's 10-page short story as much as we need it to be. And it's beside the point of the story.

But you can understand why—apart from the exigencies of the popular cinematic form—screenwriters would be tempted to expand so extensively on the original. "The Killers" is a story driven by challenging readers' expectations. It begs you to imagine what's going on behind the scenes. It must have been impossible not to give in to that impulse.

"The Killers" was known to be a favourite story of the author's and perhaps this is why. Hemingway, of course, was famed for his understated style that hides and barely hints at volcanic emotions rumbling under placid human landscapes. It was almost a game with him to see how much he could suggest without telling.

Having it both ways

At first the suspense is created as in a conventional crime story by the activity of the strangers in the diner. Who are they? What are they after? Who sent them? Are they going to kill the diner's inhabitants? (Probably not all of them, since one is Nick Adams—a protagonist in a whole series of stories and considered a stand-in for a young Hemingway—but it seems quite likely that diner owner George and the black cook, Sam, referred to in the racist vernacular of the time, could be eliminated as witnesses.) Will the Swede they seek come walking in to meet his death?

This tension is suddenly lifted as the killers give up waiting in the diner and depart without hurting anyone there.

But then the real game begins. Nick's encounter with the Swede, whom he tries to warn, goes quite differently than expected. The only hints of explanation we're given are a few cryptic remarks from the doomed man about not running any more and speculation back at the diner that he must have double-crossed somebody because "That's what they kill them for."

And that's all we need really. For the precise explanation is not important.

What is significant is the Swede's stoic, if fearful, acceptance of his own fate, his expectation that he'll be dealt with for having broken some code, however crooked.

Even more importantly, Nick learns that others will accept it too. Not because they agree with it but because it's someone else's code and there's not much in any case they can do about it.

Hemingway may be criticized for wanting to have it both ways. His (that is, the character Nick's) idealism and desire to help is admirable, but his (that is, the author's) patented cynicism is vindicated once again. Nick may have to leave town to protect himself.

The last line may be Hemingway's ironic joke against himself.

You don't have to think about such awful things, he says. Though he just made you do so.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes