The Other Woman

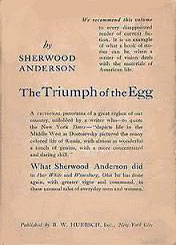

Story collection first edition, 1921

Story collection first edition, 1921First book publication

1921 in collection The Triumph of the Egg: A Book of Impressions from American Life in Tales and Poems

Literature form

Story

Genre

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 3,500 words

Facing the other in oneself

"The Other Woman" is a story that may explain why modernist writers like Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner looked up to Sherwood Anderson at the beginning of their careers, though they later felt it necessary to move on from his influence.

It's a pretty great short story. Very well crafted, in a way that broke from the great, well-crafted stories of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth literature. It's a story that heralds the coming literature of the post-Great War generation.

There's the psychological element. The narrative is almost, but not quite, stream of consciousness. The speaker rattles on through the pages, giving voice to the flow of thoughts passing through his mind as he relates his impulsive cheating on his fiancée, later his wife—contradicting himself at several points, occasionally losing track of the point he's trying to make, and even creating an impression opposite to what he obviously intends to convey in the mind of the listener. But technically he's not the narrator of the story, as there is an listener to his tale, at least in the first couple of pages—although this anonymous, first-person stand-in for the reader soon disappears and the speaker carries on directly to us, without interruption.

The speaker is obsessed with explaining himself—another modern characteristic. I've heard others describe the speaker in the story as diligently examining his own psychology, trying to develop a new morality. But it seems obvious to me that this is an act. He's trying to impress the listener that there is nothing radically wrong with his behaviour.

Of course, he's compulsively talking to convince himself in the first place. The distance from the story's first line in which he defends himself against an accusation that is never made to that last line, which denies any deep effect, is short. This is no journey of discovery, but rather a psychological cover-up.

On the other hand, I can see how some readers may take greater significance from an apparent lack of repercussions from his actions. That is, maybe he really is in love with his refined, independent wife while happily carrying on a carnal relationship with a less challenging woman of lower status.

We could also take the speaker's affair to represent his reaction against his bride's rather effete brand of feminism. The "awakening woman" requests they live together not as man and woman but as human beings, until his patience and kindness can teach her the way of life, so that someday they can love with passion. I'm not sure what that means, but neither does it excite our bridegroom.

We could even read this story as an early confused, exploration of an alternative lifestyle—way ahead of its time.

Writing without frills

And maybe this is the appeal of "The Other Woman"—that Anderson is not laying out one way we're supposed to take the story. We can empathize with the untrustworthy speaker, or not. It doesn't really matter. Morality is somewhat beside the point. This is just a normally frail human being trying to rationalize his own behaviour that has taken even himself by surprise.

The unreliable narrator would become a staple of literature over the twentieth century. In some popular fiction, it's just a technique of misdirection, letting the author hide certain elements of the plot from the reader until the truth can be sprung in a surprise ending. But in more sophisticated writing, the unreliable narrator allows just what we find in "The Other Woman": complexity, uncertainty. Which may not entertain as much, but makes us think and rethink. To examine and re-examine our own feelings.

This may seem a big burden to place on such a short story written so unpretentiously. (That is, Anderson's writing is unpretentious. The character in the story, however, is full of pretense.)

Writers like Hemingway admired Anderson's craft but came to resent the subjectivity of Anderson's writing. He and others learned from their mentor to write directly—"without frills," as it is sometimes described—but they developed a starker, darker, harder-boiled, more objective style, even when implying psychological or emotional depth and when portraying strong sentiments like love.

Still, "The Other Woman" and other early short pieces by Sherwood Anderson stand as intriguing works in their own right, as well as show the way ahead for many great stories to come.

— Eric