The Tale of Sinuhe

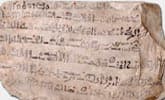

Tale of Sinuhe ostracon

Tale of Sinuhe ostraconAlso known as

Sinuhe, The Story of Sinuhe

First publication

c.1875 BCE

Literature form

Story

Genre

Adventure

Writing language

Middle Egyptian

Author's country

Egypt

Length

Approx. 19,000 words

Ancient adventure the first novella?

We know only a handful of ancient Egyptian stories, as opposed to ancient laments, instructions, prayers and the like. Even fewer of those have come down to us in complete form. "The Tale of Sinuhe" though has been preserved in more copies than any other work from that period.

It was apparently popular in those old times. And no wonder.

"The Tale of Sinuhe" is the ancient Egyptian story that comes closest to what later would become epics or, in modern times, novels. While "The Shipwrecked Sailor" and "The Eloquent Peasant" turn on single themes and incidents, like later folk tales or modern short stories, the Sinuhe narrative has a wider canvas. We follow one character (whose name Si-nuhe means "son of the sycamore") through several countries and, more importantly, through several crises and changes in his life.

The text in English is still only a dozen or so pages long—short-story length by our standards—but packs a lot into those pages. Sinuhe is a servant in the royal harem when he learns the pharaoh has been assassinated, Sinuhe panics over the prospect of ensuing violence and flees Egypt. After minor adventures in several countries he takes up residence with a friendly ruler in "Asia" (probably what we call Syria now), where he gains great power. At one point he faces a formidable foe in a one-on-one duel that some think is the inspiration for the David and Goliath story in the Bible. However he pines for his homeland and petitions the reigning pharaoh, son of the deceased ruler, to let him return to spend his last days in Egypt. Having made good abroad, he's forgiven in his native land for unnamed offences (possibly for having been involved in the previous monarch's death) and welcomed back with riches.

There's a lot about the importance of dying at home so his burial can be carried out properly and allow him to be transported to eternal life on the other side. In fact, the story purports to be told in the first person by Sinuhe after his death.

Maybe that's not as grabby as the latest Russell Crowe historical movie epic. But it is the same kind of story in primitive form. There's a thrill for modern readers in seeing how different from us, and yet how similar to us, someone from four thousand years ago can be. An old story in which the sentiments and behaviour are completely alien to ours would have no attraction, and one in which people think and act exactly the same as we do would hold only moderate interest. But the combination of foreign and familiar is intriguing as it makes us question the common elements in human experience.

That may be putting too fine a point on it. You either dig this kind of stuff or you don't. But give it a try. Read several versions of this story along with other ancient Egyptian works and you may find yourself dreaming about life in other times and places.

You can download free versions of this and other ancient Egyptian stories online, although these tend to be dated translations. Recent translations in books make for smoother reading and take into account more complete research. Two very good compendiums—and with great notes explaining the difficult bits—are The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Egyptian Poems, translated by R.B. Parkinson, and The Literature of Ancient Egypt, edited and translated mainly by William Kelly Simpson. As the title implies, the former renders all the works in poetry but don't let this put you off; it's very readable poetry, not much different from prose as far as I can tell, except the lines are shorter. Simpson uses both forms; his "Sinuhe" is in prose.

The Sinuhe tale is also retold in modern novelistic form in The Egyptian (also known as Sinuhe, the Egyptian), by Finnish writer Mika Waltari, who expands the story and moves it several centuries ahead to include Sinuhe's relationship with monotheistic pharaoh Akhenaton. The highly praised historical novel first appeared in 1945 and it has been reprinted in English as late as 2002.

An historically inaccurate film adaptation of the Waltari novel, The Egyptian, appeared in 1954, directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Jean Simmons, Victor Mature, Gene Tierney and Peter Ustinov. The Hollywood movie makes Sinuhe and Akhenaton out to be precursors of Christianity, which was still a millennium and a half in the future.

— Eric