The Man Who Would Be King

Critique • Quotes • Text • At the movies

The Phantom Rickshaw first edition

The Phantom Rickshaw first editionFirst publication

1888 in The Phantom Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales

Literary form

Story

Genres

Literary, adventure

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 14,500 words

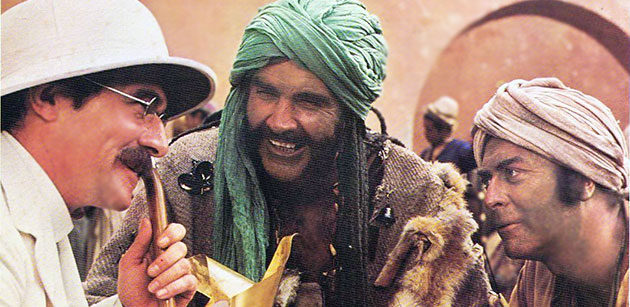

Christopher Plummer finds Dravot (Sean Connery) and Carnehan (Michael Caine) disguised.

Of kings and good hearts

The Man Who Would Be King (1975): Film, 129 minutes; director John Huston; writers Huston, Gladys Hill; featuring Sean Connery, Michael Caine, Christopher Plummer, Saeed Jaffrey, Shakira Caine

If Rudyard Kipling is waxing semi-satirical in his story "The Man Who Would Be King", I'm not sure director John Huston or his stars in the adaptation know that.

The film has several humorous episodes, but for the most part Sean Connery and Michael Caine play their parts straight. And darned if it doesn't work magnificently. In fact much of the fun comes from them not overtly playing it for laughs.

They're two adventurers putting in heroic efforts to accomplish rather self-serving ends. Former sergeants Daniel Dravot and Peachy Carnehan maintain the spit and polish of appearance and the discipline of British soldiers in their mad quest, charming even the newspaperman, supposedly Kipling (Christopher Plummer), despite his misgivings.

Among the delights of the first half of the movie are Daniel and Peachey proudly displaying to Kipling their "contrack" committing themselves to each other, forgoing drink and women, in their quest for king-hood, and the scene of synchronized duo smartly marching into and out of the office of a British official who wants to jail or expel them but can't because they've managed to blackmail him—"Hats on! About turn! By the left! Quick march!"—leaving witness Kipling having to stifle his laughter.

He is further entertained when he later finds them disguised as Indians, playing the fools, to make their way toward their constant goal.

But despite all the entertaining scenes, eventually it becomes clear the two scoundrels are supposed to represent the indomitability of the human spirit or some such thing. Dreaming the impossible dream and making it happen. Somewhat naďve and flawed so as to eventually fail, but for one brief moment achieving something magnificent. Heroic.

Daniel and Peachey lay out their big plans in a scene from The Man Who Would be King.

You'd think this lofty would be undercut by the viciousness of some of their actions, their subjugation of peoples, and all the other colonialist delusions for which author Kipling is criticized.

And, indeed, there are several uncomfortable moments in the latter half of the film when it strikes home this is not just an enjoyable adventure but real people are getting hurt. And there are times when the tawdriness of the men's ambitions become too apparent and you may wonder, "Why am I cheering on these guys? Why do I find them so appealing?"

But largely, Huston and his stars get away with it. It's just put together—written, directed and acted—so well. You even feel admiration for them when they face their ends. You are shocked, as the character Kipling is, at the final reveal.

You know you shouldn't feel this, but you do.

I wonder if this ambivalence created in the audience is what kept The Man Who Would Be King, one of the best movies of all its famous principals, from being a huge hit at the time and keeps it even today a bit of a guilty pleasure.

This well-crafted movie is a bit of a throwback to earlier days of Hollywood. It's not surprising to learn the project had been around for a couple of decades and originally was intended to star Clark Gable and Humphrey Bogart. It would have fit into Huston's early and middle-period run of films—including The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) to Beat the Devil (1953)—featuring dubious figures in ill-fated quests for riches.

By the time The Man Who Would Be King was produced, though, we'd come to the end of problematic Kipling works being adapted for movie theatres.

— Eric