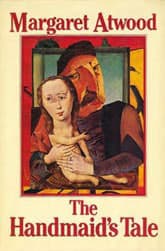

The Handmaid's Tale

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1985

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary, philosophical, science fiction, dystopian

Writing language

English

Author's country

Canada

Length

Approx. 109,000 words

The sexual counterrevolution

If you're well-versed in science fiction—or speculative fiction as it's often called—and you approach The Handmaid's Tale as an example of that genre, you may be disappointed. The world of Margaret Atwood's most popular novel is not conceived particularly innovatively compared to the future worlds imagined by science fiction's modern masters. Which may be the point of The Handmaid's Tale with its "this could happen here" message.

Now, the extrapolation of existing trends into society-wide dogma have long been staples of SF. Nor is the idea that a conservative backlash against progress might grow into a distorted kind of Christian-Right dystopia a new one.

It is not developed very credibly in The Handmaid's Tale. The depiction of oppression focuses almost entirely on the role of women as housekeepers and baby-makers in the former United States, now called the Republic of Gilead. (Gilead, by the way, is the setting in the Old Testament for the story of Jacob who used his wife's maid as a surrogate mother for his children, as quoted in the novel.) We don't see how this state of affairs came about nor get any idea of all the other massive political and social upheavals that must have been involved in this revolution.

But if you come to the book not from the world-building speculative perspective but looking for a cautionary feminist tale from a writer known more for her mainstream literary works, you may find the story appropriately chilling.

Bizarre ritual

Atwood's interest, as usual, is in the power relationships between the sexes. But even this is incredible in the novel. The ritual, for example, by which high-ranking men mechanically fornicate with slaves, known as "handmaids", while the latter are held between the legs of the official wives in bed is awkward and ridiculous. According to Atwood, everything in this dystopian novel is supposed to have been found in the real world, so we'll have to stipulate this horrendous behaviour has taken place somewhere or sometime. But the author is still on the hook to make it appear plausible as an eventuality in the world we do know. It's hard to imagine any party to the tryst going along with the setup. Yet somehow, in only a very few years, this fictional society has overthrown or adapted existing American society to make this form of procreation the norm.

But how we got to this point is not of interest in the novel. Atwood and her readers are willing to stipulate the victory of religious right-wingers in order to proceed with this thought experiment examining the position of women.

What it tells us

As a narrative, The Handmaid's Tale doesn't go much further than that. What there is of a plot is designed chiefly to get the heroine, Offred (her patronymic Gileadean name from "of Fred", as her real name is never revealed), around enough to show us the various ways women are treated in this projected world. When the tour is complete, the conclusion is thrown together quickly.

Then why is this novel so highly regarded?

It does tell us something about the plight of women. Half the readers may find this to be exaggerated nonsense but the other half likely find it revelatory. And I don't think the division is necessarily along gender lines. Some liberated women are likely repulsed by what they see as revelling in victimhood, and some liberated men will feel guilt over what they recognize as their fellows' attitudes reflected in the rulers of Gilead.

Atwood is also very good at drawing the reader into a character's inner world with telling details of daily life that other authors would miss. We do care about Offred. As much as we can, that is. Throughout the novel, the thought recurs: when is she going to actually do something to fight back? A vain hope, it turns out. Even her final possible escape (or is it her doom? the ending is ambiguous) is not of her own doing but at the hands of a male rebel (or agent).

A novel has to be more than a character study or social inquisition. In creating The Handmaid's Tale, Atwood was influenced by George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, another novel whose plot exists mainly to show us around an alternative world, thereby revealing our own. Nineteen Eighty-Four, though, goes deeper into that other world, and thus deeper into our own.

Much as I have problems with Nineteen Eighty-Four, by the end of that story I am provoked. By the end of The Handmaid's Tale, I am amused but unmoved.

Except the end of the story is not the end of the novel. After Offred's first-person account of her life as a handmaid, Atwood has added a clever chapter in which future academics discuss the diary we've just read. It too is apparently inspired by Orwell's book which also features appendices. However, it comes across as a last-minute attempt to add historical context. Too late. What is really wanted is a better story along the way.

An update:

Many of the criticisms expressed here, especially over not putting Gilead in historical context or showing the women fighting back, are addressed in the much later sequel, The Testaments (2019)

Three women, two in Gilead and one in Canada, narrate their resistance struggles in this Booker-winning novel. Strong story lines distinguish the sequel from the original. They engage and provide much needed hope after the dismally uncertain conclusion of the first book.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies