The Odyssey

Critique • Quotes • Translations

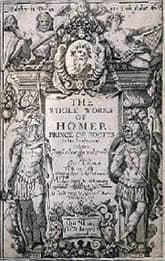

The Whole Works of Homer, trans. Chapman, first edition, 1616

The Whole Works of Homer, trans. Chapman, first edition, 1616First publication

c.800 BCE

Literature form

Poem

Genres

Epic poetry, mythology

Writing language

Ancient Greece

Author's country

Greece

Length

24 chapters, approx. 12,000 words

The original crowd-pleaser

This one has it all. The Odyssey is not only a great romantic, adventure epic, but it's terribly realistic in its depiction of human nature within a brilliantly crafted narrative. Authors today could learn from how Homer (whoever he was or they were) lays out the plot and plays the characters off against each other for maximum reader involvement.

Of course it was composed almost three thousand years ago and our sensibilities have changed a little over those centuries. So the Odyssey doesn't exactly go down as smoothly as the latest bestselling novel. You have to work a bit at putting yourself in the ancient mindset and understanding it, especially if you're reading The Odyssey translated as poetry.

But when you do make that effort, you'll find it starts coming easier and easier, and it ends up seeming not so ancient or foreign after all. It eventually sucks you right into the tale.

Which is more than you can say about many "classics" of more recent vintage—to wit, James Joyce's novel Ulysses, which supposedly follows Homer's outline.

Anticipating adventure

Homer is way ahead of his time in the indirect route he takes in telling the story. The standard approach to an epic is to start in medias res—in the thick of the story, as the same author does with the Iliad. But instead of setting off with Odysseus (also translated as Ulysses) at the fall of Troy, picking up from the end of the Iliad, and following the character's ten-year journey home from the war, here Homer starts near the end of the story.

We're shown the state of Odysseus's home and family, with suitors for his wife Penelope despoiling his estate. His son Telemachus is sent by the gods to find his father, and has several adventures of his own over the first four chapters. (It's thought by some scholars the Telemachus story was once a separate work that was later joined with the Odysseus tale, while others think Homer intentionally used this diversion to build up anticipation and show the roles of the gods in the story to come.) Telemachus finally learns his father has been kept captive on an island by the nymph Calypso.

Then the narrative switches to Odysseus. With the help and hindrance of various gods, he escapes from the island, is almost drowned and is washed up in another land where he stays anonymously. Eventually he reveals his identity and he starts—in what's designated as the ninth chapter of The Odyssey—recounting all that happened to him since the Trojan War to bring him to this point. Here we get the adventures we've all heard before: visiting the land of the Lotus-Eaters, fighting the Cyclops, escaping the cannibals, descending into Hades, outsmarting Circe who turned his crew to swine, evading the Sirens who lure sailors to their death, passing between the monsters Scylla and Charybdis, being captured by Calypso.... Told over four action-packed chapters, this brings us up to present.

The rest of the tale concerns the homecoming of Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, and his bloody revenge on the interlopers. Plus a little extra excitement at the end as a civil war erupts before the gods can impose a peace.

It's all exciting stuff. But significant too in how it depicts a hero. Odysseus is not just an honest, just, god-fearing action hero. He's crafty, a trickster. At times his morality is repugnant, at least to a modern audience. He displays the vengeful anger and self-righteousness that you also find in Old Testament gods and prophets, mixed with promiscuity, greed, and single-minded self-interest—and tenderness, especially in regard to his wife and son. It's a complex mix but it works. Much more interesting than the forthrightly self-righteous characters of the Iliad.

A human hell

Another nice thing about this tale, in contrast with the Iliad, is that the gods are relatively laid-back. Apart from Athene, who gives Odysseus a hand now and then, most of them are not constantly interfering. They leave the mortals to work out their problems in their own bloody or lovable ways.

One of the most intriguing escapades in which Odysseus takes part is his trip to the underworld, the afterlife abode known as Hades, where he meets the shades of his mother and former comrades in the Trojan war, Achilles and Agamemnon.

It may seem strange to a modern reader how different this place is from our notions of heaven and hell. For one thing, it offers no reward or punishment for how one lived. Every mortal ends up sharing the same miserable kind of half-life after death. This is similar to the netherworld visited in the Babylonian Gilgamesh epic, probably written well before Homer's account, and in other mythological tales of the time.

The tour of hell would also become a common subject of later ancient, medieval and renaissance writers—Virgil, Dante and Milton come to mind—but in their hands the terminus of human life would gradually split into multiple destinations where the dead would reap the appropriate retribution for their good or wicked lives—closer and closer to a latter-day Christian version of the afterlife. (I say "latter", because no clear mention of heaven or hell for individual retribution can be found in early Judaic-Christian writing, including in the Old or New Testament.)

Stock phrases

As always, the translation one reads can have a great effect on how much you get from such a story. Check the commentary on Odyssey translations for a brief comparison.

One thing that may put you off is Homer's use of certain stock phrases. The water is always "the wine-dark sea", daybreak is always "rosy-fingered dawn", and certain characters always arrive with the same adjectives before their names. Not all translations retain this repetition, but if you do find it, bear in mind that these stories were meant to be recited or performed from memory rather than read, and the repetitions helped to fix certain images and characters in both the storyteller's and the audience's memories.

Try reading it aloud to yourself and, at least with some translations, you may discover how much more understandable and enjoyable it is.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • Translations