Don Quixote

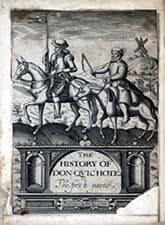

First English edition frontispiece, 1620

First English edition frontispiece, 1620Original title

El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha

Also known as

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, or The History of Don Quixote, or The Adventures of Don Quixote of la Mancha

First publication

1605–1615

Literature form

Novel

Genre

Literary

Writing language

Country

Author's country

Spain

Length

Approx. 395,000 words

Slogging through an earthy classic

First, get refined ideas of "classic" out of your mind when you approach Don Quixote. For, as with many of the greatest works of prose literature, this is a lively, earthy story of flesh-and-blood people.

Sure, the central character is a bit of a kook whose very name has become synonymous with fighting imagined evils (literally tilting at windmills in his case) and has given rise to an adjective—quixotic—having to do with the pursuit of impractical ideals.

And, sure, he believes he is a chivalrous knight, his broken-down nag is a noble steed, the slovenly peasant Sancho Panza is his squire, and a whore is the lady Dulcinea needing to be rescued.

But we the readers are shown the world realistically, and the people in it—including the deluded main character—as they really are.

In the prologue to the first part of Don Quixote, author Cervantes says he aims to destroy through satire the influence of chivalric romances on the people of his time. His elderly Don Quixote has supposedly gone mad from reading too many such tales and sets about to emulate the adventures of knights—with ridiculous and pathetic results. The comic chapters showing his misadventures are indeed quite entertaining, and these are the bits that have entered popular culture—windmills and all.

Those bits, however, are strung out over many pages of subplots and digressions into other tales that hold the interest less tightly, at least for a modern reader who may not recognize half the targets of satire. Too much poetry recited by lovesick shepherds and goatherds. It's a long, hard slog to get through Part One.

Setting the template

Part Two, written by Cervantes ten years later, picks up the pace somewhat and actually makes the central character and his loyal servant much more interesting. Don Quixote and Sancho become less figures to make fun of than fully fleshed and endearing human beings.

The story becomes more than Cervantes perhaps originally intended.

Still, this is a book that cries out for someone to produce an abridged version for the modern reader—something I usually frown upon. Don Quixote has so much to offer, but a thousand-plus dense pages of a four-hundred-year-old satire is more than many of us can sit through.

But, in whatever form, Don Quixote is worth it for the serious student of literature. The book has had a tremendous affect on our culture, not just in advancing the novel form and setting the template for several of the early types of modern writing, as well as for both the romantic and the anti-romantic modern attitudes toward literature.

Like Shakespeare, Cervantes has provided many of the very words and phrases we still use today. Among the dozens of expressions Don Quixote is credited for originating or popularizing are, in English translation, "too much of a good thing", "plain as the nose on a man’s face", "out of the frying pan into the fire", "murder will out", "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush", "faint heart never won fair lady", and "with the sweat of my brow" (though this one first appeared in the Bible's Old Testament).

Online you can also find all kinds of ringing quotes attributed to Don Quixote, about trying to reach unreachable stars and about sanity consisting of seeing the world as it should be. But these inspirational messages are actually from plays, movies or songs only loosely based on the novel. Cervantes's original words are much clearer-eyed and sharper.

I suspect a lot of students over the years have written essays based on those other cheerier works instead of working through Don Quixote's sometimes thick prose.

I can't really blame them, but—well, their loss.

— Eric