Fahrenheit 451

Critique • Quotes

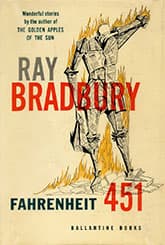

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1951 as novella The Fireman in Galaxy Science Fiction

First book publication

1953 as Fahrenheit 451

Literary form

Novel

Genres

Science fiction

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 48,000 words

Burning questions

It may seem Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 is becoming less relevant these days, as hard-copy books are at risk of disappearing, pushed aside by digital communications. Without paper media, warnings about book-burning might become archaic.

For book-burning is what Fahrenheit 451 is generally thought of as being about. For good reason.

The name of Bradbury's original short story upon which he based the novel was "The Fireman", and the title of the novel refers to what Bradbury claims is the temperature at which paper burns ("claims" because an argument has blazed online over the figure). The narrative deals largely with the fire department searching out books to set alight, with one fireman, Guy Montag, coming to question what he does and actually starting to read the objects he's been destroying.

Yet Bradbury goes way beyond book burning in Fahrenheit 451. He has an obvious affection for printed books and a horror of losing them to flames, but he makes a point of stating he doesn't venerate the objects themselves but their contents:

"It's not books you need, it's some of the things that once were in books.... The same infinite detail and awareness could be projected through the radios, and televisors, but are not. No, no, it's not books at all you're looking for! Take it where you can find it, in old phonograph records, old motion pictures, and in old friends; look for it in nature and look for it in yourself. Books were only one type of receptacle where we stored a lot of things we were afraid we might forget. There is nothing magical in them at all. The magic is only in what books say, how they stitched the patches of the universe together into one garment for us."

Return to storytelling

Censorship of the kind of expression found in books—and potentially in other media—is closer to what we are being warned against. The rebels in Fahrenheit 451 seek the response to the literary holocaust not in printing more books but in committing books' contents to memory. Essentially they return to a preliterate, oral, storytelling society. Only in some distant future day—they seem to be in no rush—might it be practical to set it all down in text again.

But even this is not the whole story, so to speak. What's all that about magic and stitching the universe together?

Even if you haven't been reading closely, partway through Fahrenheit 451 you must realize our protagonist Montag suffers from more than doubts over his career as a legal arsonist. His wife lives in a frivolous world of televised non-reality and drugs herself to sleep every night, nearly to death at least once. He never has an honest discussion with any of his family, colleagues or neighbours (except with one free-spirited seventeen-year-old girl—who soon disappears). In their fast-moving consumer society they're disconnected from both nature at large and their own human nature. Everyone lives in fear of impending nuclear war. Montag lies awake at night, desperately unhappy.

It's simplistic to say his malaise is all due to not having books to read. But as Montag's day-to-day existence is fitted into the narrative between the book-burning episodes, it becomes clear that it's all part of the same pattern. A society that does not allow ideas and stories to be shared is one that cannot give its people a meaningful life. And vice versa.

Yet this horror is delivered with Bradbury's patented poetic, almost whimsical touch. He never beats you over the head with the connection of book-burning and social alienation and the war, etc., but he leaves it in questions in Montag's mind.

Poetic horrors

I can't think of any other writer who can portray dystopia as lightly as he does. Certainly not George Orwell who produced Nineteen Eighty-Four in the same era and certainly not more recent writers like Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid's Tale or Cormac McCarthy in The Road. I'm not saying Bradbury treats human and social disaster lightly, as he never shies away from the tragic elements. But his allegorical style, his imaginative metaphors, his language choices paint the personal experience more economically than any detailed list of horrors. Note how he introduces Montag's discovery of his comatose wife:

Her face was like a snow-covered island upon which rain might fall, but it felt no rain; over which clouds might pass their moving shadows, but she felt no shadow. There was only the singing of the thimble-wasps in her tamped-shut ears, and her eyes all glass, and breath going in and out, softly, faintly, in and out her nostrils, and her not caring whether it came or went, went or came.

Followed shortly by war planes flying overhead:

As he stood there the sky over the house screamed. There was a tremendous ripping sound as if two giant hands had torn ten thousand miles of black lines down the seam. Montag was cut in half. He felt his chest chopped down and split apart. The jet bombers going over, going over, going over, one two, one two, one two, six of them, nine of them, twelve of them, one and one and one and another and another and another, did all the screaming for him.

Bradbury is sometimes criticized for such passages being too verbose or flowery. But their images substitute for several pages by more expository writers trying to impart the sense of how events strike the protagonist. Bradbury's repetition of phrases, his ironic inversions, his mirroring sentence structures—many of his techniques are drawn from the concisely expressive literary form of poetry.

A criticism of Fahrenheit 451 I do have, however, is the same criticism I have of many science fiction dystopias. It fails to adequately expose the forces that led—or could lead—to these dire circumstances. Like many such works, it extrapolates upon selected social phenomena today to show what could happen if these trends are carried to extremes. But in reality there are always contradictory trends in place; what economic factors inexorably lead to this one-sided outcome or what social group finds it in their own interest to push for this trend? Without this, we are left with a vague sense that, well, people just started acting more and more this way, or governments just began acting more and more totalitarian...until we found ourselves in this mess. The same complaints apply to science fiction utopias, which often seem to come about by people and their societies just becoming better and better without cause.

Today we have trends toward censorship, war, consumerism, inequality, and more bread and circuses to distract the citizenry as in Fahrenheit 451. But we also have movements toward tolerance, civil liberties, peace, equality and, as in the writing of Ray Bradbury, a search for more enriching culture. Over the years, the pendulum tends to swing back and forth between these counterbalancing drives with slow overall movements in one direction or another. What—or who—causes a radical shift exclusively toward one side or the other? If we're to avoid the outcomes in Fahrenheit 451, it'd be good to know.

But at least Fahrenheit 451, better than most dystopian fiction, effectively warns us against what could happen. It goes beyond book-burning or censorship to prod us to examine our lives, to question the meaning in our lives.

It may be a pleasure to burn, as the opening lines attest. But, as a seventeen-year-old girl asks, "Are you happy?"

— Eric

Critique • Quotes