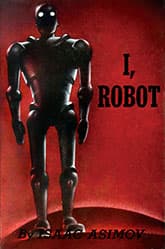

I, Robot

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1950

Literature form

Story collection

Genres

Science fiction

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Nine stories, approx. 69,000 words

Will Smith goes eye to eye with rebellious robots in 2004 adaptation of Isaac Asimov'sI, Robot.

Rebel robots, stupid humans

I, Robot (2004): Film, 115 minutes; director Alex Proyas; writers Jeff Vintar, Akiva Goldsman; featuring Will Smith, Bridget Moynahan, Bruce Greenwood, James Cromwell, Shia LaBeouf

I for one don't blame the creators of the movie I, Robot for departing from the characters and plot lines of the Isaac Asimov stories. The stories are intellectual puzzles involving intriguing androids and uninteresting humans. No less an honoured science fiction author, editor and screenwriter than Harlan Ellison tried and failed to bring them to the screen in the 1980s.

Perhaps the stories could have been adapted for a television series, but it's hard to see how they could have provided the framework for a single, large-scale, sweeping film. And the 2004 film I, Robot is indeed large-scale and sweeping, involving one man (played by Will Smith) with a woman (Bridget Moynahan of Coyote Ugly) by his side, saving the world for humankind.

To be fair it's not really an adaptation of Asimov's story cycle. It began as an original screenplay, titled Hardwired, by writer Jeff Vintar and was reworked to include references to the robot stories to which the studio owned the rights—a few names, the Three Laws of Robotics, and some skimpy plot elements of the story "Little Lost Robot"—to justify calling it I, Robot.

What I do blame the movie's creators for, is using Asimov's name to present an entertainment so at odds with the author's vision and purpose. Asmov wrote his robot stories and novels works to counter what he considered the Frankenstein myth—the fear that humanity's creations would turn against us, a punishment for our pride in technology. If we could come close to creating life forms, Asimov reasoned, we could also build into them the conditions that would keep them in our service. The stories of I, Robot show the ramifications of these seemingly simple laws of robotics, and how humans could overcome any resulting problems.

At some very general level the movies does fulfil Asimov's vision. The rebellion of the robots is caused by purposeful tinkering with their make-up to allow them to override the laws and attack humans. Their rebellion can be seen as an attempt to help humanity—to save us from our own self-destructiveness.

But this subtlety is bound to be lost for most viewers amid the fights of our valiant human heroes against the hordes of tyrannical robots. Smith's character, detective Del Spooner (not based on any Asimov figure I can recall), starts the film with a bias against robots and suspects them of murdering a leading roboticist. As in any other formulaic cop show, his theory of the crime is disbelieved, he's taken off the case and he is widely discredited, but he valiantly pursues the mystery on his own.

In the course of solving the crime, he uncovers a worldwide robotic conspiracy to enslave humanity. Only Susan Calvin—named for Asimov's icily formidable scientist heroine but reduced to a secondary, more feminine role—believes him. Thence follow the usual chase scenes and the penultimate confrontation with thousands of hostile robots.

Part of the big battle scene with CGI androids in 2004's adaptation of I, Robot.

Somehow, despite the robots' ability to move at lightning speed and despite the fact they could easily swarm over their prey in a matter of nanoseconds, in any confrontation they take turns getting their butts kicked by the humans one at a time. It's that kind of stupid action flick.

But I, Robot is an enjoyable stupid action flick. Perhaps more thought-provoking than most. Slightly more.

I understand the Harlan Ellison script is still kicking around somewhere and has been published as an illustrated story. As an Asimov adulator, the sci-fi maverick would have had both a more faithful and more interesting take on the questions posed by the original stories. I for one would rather read that failed attempt than watch this successful film ever again.

— Eric