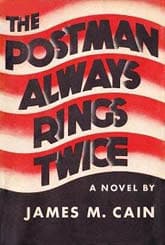

The Postman Always Rings Twice

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1934, United States

Literature form

Novella

Genres

Literary, crime

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 38,000 words

Nick (John Colicos) celebrates with wife Cora (Jessica Lange) and Frank (Jack Nicholson).

The Postman in dark colours

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981): Film, 123 minutes; director Bob Rafelson; writer David Mamet; featuring Jack Nicholson, Jessica Lange, John Colicos, Michael Lerner

On paper the remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice in 1981 sounds good. It updates the story in film at a time when changing mores would allow a grittier and more sexually graphic telling of the story. Add a script by playwright David Mamet, direction by rising young maverick Bob Rafelson, and the casting of seemingly appropriate leading actors, Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange, as the scheming lovers, and it's hard to see how it could go wrong.

But it does.

There is much to admire in this adaptation. Like the 1946 film, it adheres quite closely to the Cain novel. Closer in some ways. For one thing, Nick Papadakis—not "Smith"—is Greek. He is even more openly ethnic than in the novel, a leading figure in the local Greek immigrant community.

Wife Cora Papadakis—not Smith—is still not dark as in the novel but nor is she the glamorous platinum blond of the 1946 film. Jessica Lange is naturally gorgeous but she convincingly portrays Cora as a sexy but somewhat frowsy lower-class gal. She seems just the kind of woman who would attract just the kind of man that Jack Nicholson's Frank Chambers is.

What kind of man is that? Well, definitely not likable. It's difficult to see what Nick sees in him, why he'd want to hire him. He's obviously some kind of hustler and Nicholson lacks the kind of vulnerability that Garfield brought to the role in 1946. In this role, his trademark leer and devilish grins actually turn off audience sympathy.

Frank and Cora seem not to fall in love so much as to fall in lust. Or not even that. They just seem to recognize their own rotten characters in each other.

Their first lovemaking is more like rape. And Cora visibly likes it. That first long, long sex scene in the kitchen is embarrassing. Not because it's torrid (it's not really) but because it's so demeaning and banal—a lot of grabbing and grunting and poking and sweating that goes on and on and on.

They go way beyond the hints of sadomasochism in the book. Viciousness seems to define their entire relationship. There's even an implication that they have sex at the murder scene staged to look like a car accident. (Shades of J.G. Ballard's Crash?)

The result is, despite the remake's greater realism, we are less able to identify with the lead characters.

Title never explained

Among the things to admire in this film, John Colicos (a great classical stage actor probably best known as the villain in the original Battlestar Galactica and for various appearances as a Klingon on Star Trek) is movingly deluded as Nick. Michael Lerner has a terrific time as the sleazy lawyer Katz in extended sequences of legal finagling. The entire trial and backroom scenes are carried out entertainingly by all involved.

In a departure from the book, Frank picks up not with a fair-haired, jungle-bound animal tamer but with a circus owner, played by Nicholson's own black-haired paramour at the time, Angelica Huston.

But the biggest change that upset critics is the condensing of the ending, cutting out the final trial and judgment. Some also complained the title was never explained as it was in the last scene of the 1946 movie, but this is somewhat unfair since it was never explained in the novel either.

The more important complaint in my view though is that the overall tone of the book—Cain's snappily sardonic writing—is not represented cinematically as it had been in the earlier Hollywood movie. Instead we have a sordid, dark film (despite being in colour) that dwells on misery. This is no longer jaded film noir, but hopeless modern nihilism.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

1946, 1981