The Chronicles of Narnia

Critique • Quotes

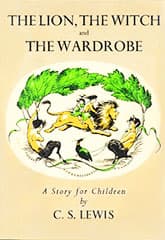

First edition

First edition• The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

• Prince Caspian (1951)

• The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952)

• The Silver Chair (1953)

• The Horse and His Boy (1954)

• The Magician's Nephew (1955)

• The Last Battle (1956)

First publications

1950–1956

Literature form

Novel series

Genres

Fantasy fiction, children's literature

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Seven novels and novellas; The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: approx. 38,500 works

The never-ending battle

Let's deal with the religious aspect of the Narnia works right off the top. The idea that The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) and its successive novels present a Christian allegory is raised by both detractors and adherents. It's offered as a reason to either dismiss or embrace C.S. Lewis's fantasy series.

One opposing author has even created a supposedly secular alternative to The Chronicles of Narnia. (That's the popular trilogy, His Dark Materials published from 1995 to 2000 by Philip Pullman, who called the Narnia tales racist and misogynist. He also wrote the controversial novel The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ in 2010, so you know where he's coming from.)

Religious folks mostly adore the Lewis stories, although some have complained Narnia is too pagan for their tastes.

Surprisingly, that latter minority may be onto something. For if the series is supposed to be a Christian allegory, it's a poor one—at least in the opening novels.

The first adventure famously begins with children in a country mansion discovering a magical wardrobe that transports them to a snowy world ruled by a wicked witch and featuring knights and animals that speak English. Sounds more like A Wizard of Oz or Alice in Wonderland than anything Biblical.

Marching as to war

As the story rolls on and the adventures pile up in subsequent stories, some Christian elements appear, but not in any consistent manner.

For example, suppose we accept that Aslan, the Lion of the first title, is a stand-in for Christ, as he's widely understood to be. Shouldn't we then expect him to spend his time wandering the land, collecting followers, healing the sick, administering to the meek and the poor, teaching prayer and faith as the roads to salvation, and rendering onto the Caesar of that world what belongs to Caesar? Instead, in the novels we find Aslan repeatedly calling for help from another world to fight the nasty forces threatening Narnia and restore to power its supposedly rightful rulers—namely members of a royal family who worship him.

We are entertained by continual bloody battle scenes with Aslan or his acolytes leading the forces on one side. Along the way we also get countless small killings, sword fights, tortures and other staples of traditional adventure stories. Little to do with the Jesus story. And much of it flatly contradicting his teachings in the New Testament.

The spirit of Narnia is closer to the mythology of the Old Testament, starring a vengeful, murderous god supporting his favoured team. Or to the European medieval period when kings ruled by the will of god. But somehow I don't think this is how those who admire the Chronicles as a Christian text want to see it.

And then there are all the other elements from pagan fantasy tales that fill the Narnia books—like witches, magic spells, talking animals, dragons, at least one unicorn—that are not usually considered part of the modern religious taxonomy.

Granted, there are some obvious Christian touchstones too, as when Aslan is apparently executed (on a stone table, not a cross) and is resurrected, as well as not-so-subtle hints of a greater power in the world and of a deeper reality accessible only to some.

But these don't make the stories all part of a thought-out allegory. They just add a few comforting symbols for certain readers. Despite being a fervent Christian, Lewis himself disdained the allegorical label for the Narnia books, saying he was writing stories about an alien world that would have familiar touches for his young readership.

His intentions

Reading through the series you might get the idea that Lewis took the Christian imagery more seriously as he went on, especially when he got to the last two written books, the prequel The Magician's Nephew (1955) and the finale The Last Battle (1956). The one throws in nothing less than the creation of the Narnian world by Aslan and the other seals the series with the end of the world and the passage of the virtuous into eternal life.

Lewis claimed he didn't intend this when he wrote The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe:

Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument; then collected information about child psychology and decided what age group I’d write for; then drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out "allegories" to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn't write in that way at all. Everything began with images: a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn't even anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord.

This still leaves us who are not believers—or who are different kinds of believers—plenty of pagan fantasy to appreciate in The Chronicles of Narnia. Perhaps a little less as the series progresses and the religious themes intrude, but still enough to keep us reading.

For one thing, these are all exciting adventure stories for kids—and kid-like adults. The narrative scarcely ever lets up.

And give Lewis credit for coming up, over and over again, with new and engaging story ideas from the same premise. Each of the seven books presents a different story—usually a different kind of story, moving through an outright fairy tale-style fantasy, an historical adventure, a sea-faring tale, a prince-and-the-pauper type of story, and so on.

Nor does Lewis exploit the same characters in every story, never relying on an easy familiarity with established personalities to draw in the readers as most fiction series do. Characters often reappear in different circumstances, but every book introduces and focuses on a somewhat revised set of characters. Even the makeup of the small group of people from our world who transfer to Narnia is modified in each adventure. And during their Narnian experiences they all tend to grow and develop in both good and bad ways.

Lewis has also perfected a charming style of writing that suits these stories, as if he's a kindly uncle relating a story that you know and he knows is only a story, but which you both pretend to believe while it's being told. And, whenever it takes his fancy, he unabashedly addresses his youthful readers directly, undercutting his characters' pretensions, sometimes even referring directly to previous books.

We the good North

It is possible though to fault the series for its blinkered morality. Lewis never explicitly acknowledges racist or even mildly discriminatory doctrines, but an unconscious Anglo-centric chauvinism runs through the works. Narnia, like the Britain from which it gets its young heroes, is a northern, wooded land while southern-dwelling creatures threaten its future.

The worst of the villainous peoples are the swarthy Calormenes (coloured men?), who appear to be some mixture of Arabs, Persians and South Asians. These "darkies," as they are called by their enemies (yes, really!), are often presented as butts of humour—you know, those funny foreigners. Meanwhile, the lily-white British kids seem fated—mainly because they are lily-white British kids—to save Narnia from the hordes and, at least for one period, to actually rule as its monarchs.

Also disturbing can be the whole aforementioned support for marching into war with God on one's side. And the slights against any progressive views on the place of women, not to mention the trivialization of one female child, Susan, who plays an heroic role in the early going but is eventually dismissed from the forces of the righteous as she grows older and becomes more interested in nylons, lipstick and party invitations.

Lewis was obviously a man of his time, or perhaps of a slightly earlier time, exhibiting in the Narnian stories many of the biases he shared with other Englishmen of his generation.

To be fair though, those who would defend him point to instances in the Chronicles when people acted against their stereotypes—when women and foreigners proved honest and valorous. Defenders also note other great authors whose work contained elements we consider racist, sexist or chauvinist.

But authors like William Shakespeare (see The Taming of the Shrew, The Merchant of Venice) or Mark Twain (see Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn) were writing much earlier of course, when it could less easily be asserted they should have known better. But more importantly the entire thrust of their works was to overcome such evils in society. The work of Lewis reeks of wanting to preserve the old ways and resisting the encroachment by any new morality. While it would be a great loss to have the works of Shakespeare or Twain taken from us to prevent the instances of offence reaching delicate eyes or ears, the elimination of the Narnian books from our shelves would seem less disastrous.

But why go to such extremes? For young fans of fantasy stories or older readers who can keep their disbelief in check, The Chronicles of Narnia and particularly that startlingly fresh first novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe can be engaging and provocative.

Read them with an awareness of what is problematic in them to get what is good in them. Then read the critics, the alternatives and the more up-to-date works in the same field. Compare and contrast. And join the never-ending discussion.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes