Julius Caesar

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

Page from First Folio, 1623

Page from First Folio, 1623Also known as

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

First performance

1599

First publication

1623 in the First Folio

Literature form

Play

Genres

Tragedy

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Five acts, 2,591 lines, approx. 19,000 words

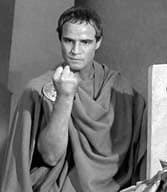

Cassius (John Gielgud, left) and Brutus (James Mason) conspire in the 1953 film of Juliet Caesar.

An acting class for stage and film

Julius Caesar (1953): Film, 121 minutes; director Joseph L. Mankiewicz; writer Mankiewicz; featuring James Mason, Marlon Brando, John Gielgud, Louis Calhern, Greer Garson, Deborah Kerr

Three or four major film adaptations have been made of Shakespeare's most famous Roman play, the tragedy Julius Caesar. One of the best is the 1953 Hollywood production of Julius Caesar that uses mainly classically trained British actors but is most famous as the classical debut of the American method actor Marlon Brando.

The film is famous for both the doubts raised before the film's release about the casting of the great mumbler as the eloquent Marc Antony and the doubts being put to rest afterwards by Brando's fierce and well-articulated performance. His determination to master the craft impressed even his co-stars, including theatre legend John Gielgud (Cassius) who reportedly offered to direct Brando in a stage version of Hamlet.

As Antony, Brando makes the most of his few but crucial appearances, including a stunningly intense delivery of the "I've come to bury Caesar" sequence at the play's turning point.

But most of this play belongs to the tortured, noble figure of Brutus. James Mason's fluid voice and minimalist acting style perfectly convey the humanity—and the tragedy of humanity—represented by this figure. His interplay with Gielgud throughout the play, starting with Cassius's cunning manipulation of Brutus into the conspiracy to kill Caesar and concluding with their reconciliation as Cassius faces death, is an acting school led by veterans of both stage and celluloid.

The bard's words

Watching this film, I understood for the first time that in the end it is Cassius who is most changed by Brutus and that because of this relationship he dies a better man than the schemer we met earlier.

Other productions of Shakespearean drama are more creatively interpreted and more spectacularly produced—and other plays are more amenable to being brought to life on the contemporary screen. But director and screenplay writer Joseph L. Mankiewicz has sculpted an almost perfect adaptation. The bard's words have been trimmed by, I would guess, about twenty per cent. But it is done so intelligently I had to check the play's text to see where any cuts were made. Everything of substance in Julius Caesar is up there on the screen.

The staging has been opened up, as they say, so it feels as if the action is taking place in ancient Rome, with its pillared streets and marbled homes, and on Mediterranean battlefields, without giving into the temptation for Hollywood spectacle.

Various bits of stagecraft persist, such as when knives and swords are plunged into the folds of togas without immediate bloodshed. This is no filmed stage production but neither is it a frenetically staged attempt at cinema verité.

The camera in this version of Julius Caesar focuses on characters in public and private turmoil, revealing (mostly) men fearing, fighting and loving each other.

— Eric