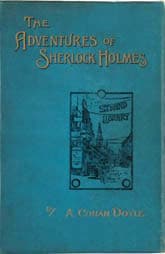

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Critique Quotes Text Sherlock Holmes at the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1892

Literature form

Story collection

Genres

Crime, mystery

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Twelve stories, approx. 94,000 words

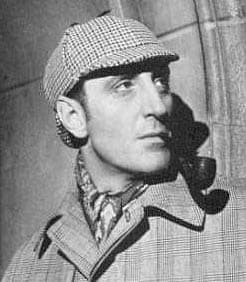

Basil Rathbone, left, solves mysteries as Holmes, while Nigel Bruce is befuddled as Watson.

The Sherlock they're all compared to

The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939): Film, 80 minutes; director Sidney Lanfield; writer Ernest Pascal; featuring Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce, Wendy Barrie, Richard Greene, John Carradine

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939): Film, 81 minutes; director Alfred L. Werker; writer Edwin Blum, William A. Drake; featuring Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce, Ida Lupino, George Zucco

Sherlock Holmes (19421946): Twelve more films; most directed by Roy William Neill; featuring Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce, Mary Gordon, Dennis Hoey

The most popular Holmes, at least for most of the twentieth century, is probably that of Basil Rathbone who, with Nigel Bruce as his bumbling assistant, starred in fourteen Sherlock Holmes movies from 1939 to 1946—as well as in more than two hundred radio dramas.

Rathbone, an accomplished stage actor, picked up many of the detective's characteristics from Wontner and others who had preceded him in establishing the figure in the public mind. But he played Holmes more intensely, he developed a new chemistry with his Watson, and he added a touch more of his own self-righteousness. As the series went on, he also updated Holmes in the harder-edged style of 1930s and 1940s film sleuths.

The result of his work is an indelibly established cinematic character we've never quite been able to shake, no matter how many fine actors have tried to redefine him.

Victorian Sherlock

The first two of Rathbone and Bruce's outings, The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939), were produced by Hollywood's Twentieth-Century Fox studio. Oddly, these are the only two in the series that take place in Victorian times.

The first film is the most famous Hound of the Baskervilles yet produced, known for its atmosphere of danger and mystery on the moors. It still thrills.

Rathbone is masterful, beginning his long association with the character that some consider the greatest ever. And Bruce is not as bumbling or comical a Watson as he became in later films.

Relatively true to the novel, with only a few liberties taken to make the experience more cinematic, their Hound is also the best of the Rathbone-Bruce series—very good for its time and still holding up today.

The second of the two Twentieth-Century Fox films actually has nothing to do with Doyle's story collection also titled The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Rather, it is based on the 1899 William Gillette play.

It opens with Moriarty being acquitted of murder, as Holmes rushes into court too late with evidence that would have convicted him. Moriarty then proceeds to present Homes two simultaneous challenges: solve a series of murders that threatens to take the life of a young heiress (Ida Lupino) and prevent the theft of the British Crown jewels.

The two leads are appealing in the roles, Rathbone adding warm touches to the icily rational detective and Bruce providing humorous relief as his none-too-bright but good-hearted colleague. The opening credits offer the conceit that what follows is Holmes's own memoir concerning the events to follow. This may annoy Doyle fans, but it is just as well since we cannot imagine Bruce's Watson being the literate and insightful recorder of his friend's exploits.

Moriarty is played by veteran British actor George Zucco as every bit a cultured, professorial figure, complete with goatee. His rivalry with Holmes is mainly an intellectual one, like a chess game, which he very nearly wins.

Despite giving the film a big production, the studio apparently had little faith in the franchise, releasing The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes with little fanfare and then cancelling planned future episodes. Yet this is the instalment I find showing up most often on television—perhaps not as darkly dramatic as The Hound of the Baskervilles, but popular as one of the best produced and involving Holmes movies of that period.

Updated Sherlock

Despite rejection by the studio, Rathbone and Bruce carried on, recreating the roles in two hundred and twenty radio dramas over the next eight years. Meanwhile, Universal Pictures brought them back to the screen with Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1942). This and the successive eleven films are updated to the 1940s to involve Holmes in more modern adventures, such as foiling Nazis in the British war effort.

The Universal flicks were inexpensively produced B-movies, each usually lasting only sixty to seventy-five minutes, and often shown as parts of double bills. But they were written, acted, directed and produced better than most B's of their era and they proved quite popular. At times the films took on an atmosphere of American film noir which was then current, though they always remained British (despite being shot in Hollywood studios) and ended happily. Even more so than in the Wontner films, the plots veered radically away from Doyle's mysteries. Many of the films had no relation to any original stories apart from the lead characters.

In Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1943), Holmes starts in Switzerland, rescuing an inventor of a new bomb-sight from German agents. But he is soon back in London protecting the inventor from an even more devious foe than the Nazis: Professor Moriarty of course. It's a fairly intense game of intrigue played out with codes (modelled on Doyle's story of the "The Adventure of the Dancing Men"), kidnapping, secret passages, and Holmes repeatedly going under cover in disguise.

The plot is certainly more interesting at least than its previous WWII entry (Voice of Terror). Both Rathbone and Bruce shine as the detecting duo, despite the displacement in time, along with Lionel Atwill as the devious professor. But what many people remember most about this film is the patriotic speech (jingoistic, some would say) Holmes makes at the end, essentially to encourage Brits to buy war bonds.

Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon is the first of ten of the Rathbone-Bruce films to be helmed by veteran B-movie director Roy William Neill, who was largely responsible for the dramatic and sombre lighting effects that gave the series a film-noirish appearance.

The most interesting of the Universal films, directed by Neill, may be The Scarlet Claw (1944) in which Holmes and Watson investigate a French-Canadian village where a murderous monster is said to be roaming the marshes—shades of The Hound of the Baskervilles. Rathbone and Bruce are at their comfortable best, easily making us anxious and making us laugh by turn. The twisting plot keeps us guessing till near the end.

Trailer for The Scarlet Claw of 1944, one of the better Rathbone-Bruce flicks.

The cheesiest of the entries may be The Woman in Green (1945), which includes elements of a couple of Doyle stories—"The Final Problem" and "The Adventure of the Empty House"—although not in any order that would make sense to a Holmes reader. Moriarty, who was supposed to be dead, orchestrates a series of murder and blackmail schemes, as well as a couple of attempts on Holmes's life. In the penultimate scene, Holmes is held captive by the villain's female accomplice who has apparently hypnotized the detective into committing suicide.

The second-last Rathbone-Bruce film, Terror by Night (1946), is not particularly terror-filled, though it does take place in that clichι of a mystery-movie locale: a train that runs all night, complete with a carriageful of suspicious-looking passengers. It is credited as being based on a Doyle story, but the only one that comes close to sharing a plot line with it is "The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax"—and the only connection is that ladies with similar names, a specially made coffin and jewels play roles in both.

Holmes is assigned to guard the fabled Star of Rhodesia diamond from a clever gang of thieves and murderers he suspects are led by Colonel Sebastian Moran, Professor Moriarty's successor. There's plenty of sneaking into and out of compartments, murders, secret identities, and twists and turns of plot. Bruce nearly steals the film with Watson's particularly bumbling, but endearing, attempts to solve the case on his own. One of the faster moving and entertaining entries in the series.

The series ends with Dressed To Kill (1946), which has very faint echoes of Doyle's story "Scandal in Bohemia". The femme fatale Hilda Courtney is compared to the woman Irene Adler, the hiding place of valuables is uncovered via the artifice of a fake fire, and both Holmes and Watson refer to the earlier case. Oh, yes, and the credibility of the English state relies on Holmes's success in retrieving certain items.

Our two leads are as game as ever in this last effort, with Bruce particularly charming, but the mystery and action are pedestrian. Much relies on Holmes decoding a music box-embedded message from an imprisoned criminal to his associates. But one has to ask: why did the convict bother encoding it in such a complex fashion instead of just telling them? After all, he had to tell them about the boxes and secret message anyway. It smacks of providing Holmes one last opportunity to play with clever codes—and not very clever at that.

In all these movies Rathbone's Holmes is more outgoing and cosmopolitan than the iconoclastic calculator of Doyle's stories. Nonetheless, Rathbone's forceful performance further established Holmes in the public imagination during the energetic war and post-War years and made his characterization the one for all future Holmeses to beat.

Many Holmes fans however find Nigel Bruce portrays Watson as too much a buffoon to be the observant literary and medical man of the books. But Bruce's comic turn keeps Rathbone from killing the movies with high seriousness and it's great fun to watch the two leads interact. In a way, Rathbone and Bruce created enduring characters quite different from Doyle's heroes—which drives Holmes purists mad but has delighted audiences.

— Eric

Critique Quotes Text Sherlock Holmes at the movies

1922, 19291933, 19311937, 19391946, 19541955, 19591984, 19621992, 1965, 1970, 19751988, 1976, 1979, 1982, 19841994, 20002002, 2002, 2002b, 20092011, 20102017, 20122019, 2015