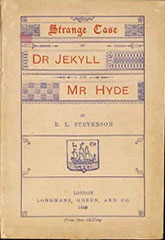

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Critique • Quotes • Text • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1886

Literature form

Novella

Genres

Literary, science fiction, horror

Writing language

English

Author's country

Scotland

Length

Approx. 24,500 words

John Barrymore kills as the first cinematic Jekyll and Hyde, the 1920 silent film.

Double lives

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920): Silent film, 79 minutes; director John S. Robertson; writer Clara Beranger, Thomas Russell Sullivan; featuring John Barrymore, Brandon Hurst

Robert Louis Stevenson's story of regressed human nature has captured filmmakers' imaginations, especially in the early days of cinema. As with Dracula and Frankenstein, which deal with similar themes, these film versions have taken on lives of their own with quite different elements from the original work.

The dramatic concept of physical transformation between Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde particularly suited itself to the visual form of the silent film and many early practitioners of the art adapted the story for the screen. One I would love to see is the 1920 film of F.W. Murnau, who two years later created the classic Nosferatu based on Dracula. As with Dracula, he is supposed to have neglected to buy the rights to Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and so his film, Der Januskopf (The Two-Faced Man), features a Dr. Warren and Mr. O'Connor. Alas, the film is said to be lost, with no copies intact.

That ham, Mr. Hyde

In the same year as Der Januskopf, the the first major American movie version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was also produced—adapted actually from an 1887 stage play by Thomas Russell Sullivan.

It's a rather plodding film, memorable mainly for the silent-screen appearance by the great John Barrymore. (See him also in one of the first Sherlock Holmes films around this same time.)

The alcoholic actor with his own Jekyll-and-Hyde public persona might have seemed a natural for the role and he makes the hammy most of the tortured doctor and his lascivious alter ego.

The transformation of one to the other is remarkable because so few special effects are used: Barrymore writhes, messes up his hair and adopts a cunning expression.

And it works. Before our eyes he becomes an entirely different being. It must have been startling for audiences in its day. That's old-style acting.

The movie opens with a printed statement:

In each of us, two natures are at war--the good and the evil. All our lives the fight goes on between them, and one of them must conquer. But in our hands lies the power to choose---what we want to be, we are.

This psychobabble sets the tone for most film treatments of Stevenson's story. We're dealing with good and evil here, a struggle between our two equally powerful natures.

A secondary theme introduced, as in the Frankenstein movies, is that the scientist in his experimenting is playing God and deserves the fate of damnation that comes to him. This too carries right through all film versions.

The film also sets the pattern for future works by following Jekyll from the start, rather than revealing his duality near the end to solve a mystery as Stevenson does.

And it introduces a love interest that isn't in the book, a young woman who pines for the handsome doctor. The doctor himself is at first a saint, devoting his life to healing the poor, and is only drawn to the dark side with the encouragement of a tempter, the girl's father. Then there's a subplot involving a bar performer and a ring containing poison.

But most of the novella's elements come into play in some way and the whole tragedy is over in an hour and seven minutes.

— Eric